Our universe is a vast and busy place, full of giant galaxies, burning stars, and deep mysteries. Scientists are like detectives, using powerful telescopes to look for clues about how it all works. Recently, they spotted an event that is incredibly violent and fascinating. Far away in a distant galaxy, a black hole was caught in the act of tearing a star to pieces. This cosmic flash was given the name AT2024tvd.

This event is more than just a star’s unlucky day. It’s exciting because of where it happened. We usually find the biggest black holes sitting right in the very center of large galaxies. But AT2024tvd is different. This black hole is an “orphan,” found wandering in the suburbs of its galaxy, far from the central “downtown” area where it should be.

This discovery is a huge clue that helps us answer a big question: Are there hidden, giant black holes roaming through the dark spaces between the stars? The story of AT2024tvd is helping us find these cosmic wanderers, one shredded star at a time. But how can a black hole be an orphan, and what exactly does it look like when it tears a star apart?

What Is a Black Hole?

Before we can understand this orphan, we need to know what a black hole is. A black hole is not an empty hole or a portal. It is an object with so much stuff (mass) packed into a tiny space that its gravity becomes unbelievably strong. Imagine crushing the entire planet Earth down to the size of a marble. The gravity on that marble would be so powerful that nothing could escape it.

This is how black holes work. Most black holes are formed when a truly massive star, much bigger than our sun, runs out of fuel and dies. The star collapses in on itself in a powerful explosion called a supernova. What’s left behind is this super dense core. Its gravity is so intense that it creates a boundary around itself called the event horizon. The event horizon is the “point of no return.” Anything that crosses it, whether it’s a planet, a star, or even a beam of light, is trapped forever. This is why black holes are “black.” They don’t reflect or give off any light, making them completely invisible.

There are two main types of black holes we know a lot about. First are stellar-mass black holes, which are the ones made from a single dead star. They are usually 5 to 100 times the mass of our sun. Second are the supermassive black holes. These are the monsters. They are millions or even billions of times more massive than our sun. Scientists are very confident that one of these supermassive black holes, named Sagittarius A*, sits at the very center of our own Milky Way galaxy. In fact, we believe almost every large galaxy in the universe has one of these giants at its heart, holding everything together.

What Happens When a Black Hole “Eats” a Star?

A black hole is invisible, so how do we find them? We can’t see the black hole itself, but we can see the chaos it causes when something gets too close. Black holes don’t “suck” things in like a vacuum cleaner. You would have to get very, very close to one to be in danger. But if a star happens to wander too close, it will have the worst day of its existence. This is the event we call a Tidal Disruption Event, or TDE.

This is what happened with AT2024tvd. A star, minding its own business, drifted too close to the orphan black hole. The black hole’s gravity is so extreme that it pulls much harder on the side of the star closer to it than it does on the side farther away. This difference in gravity stretches the star. It’s the same idea as the moon’s gravity causing ocean tides on Earth, but taken to an insane extreme.

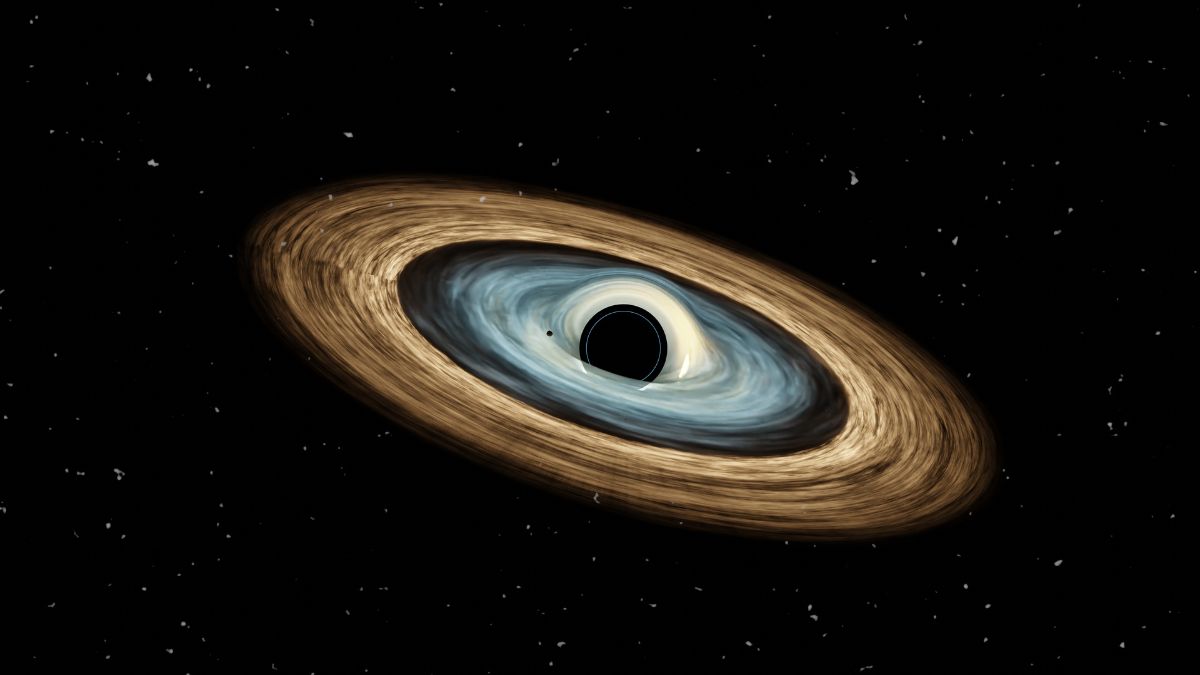

Astronomers have a famous and slightly silly name for this: “spaghettification.” The star is literally stretched and pulled apart into a long, thin noodle of hot gas and plasma. Some of this gas stream is flung away into space at high speed. But the rest of it, the “spaghetti,” gets captured by the black hole’s gravity. It can’t fall in all at once. Instead, it swirls around the black hole, forming a super hot, bright ring of material called an accretion disk. This disk is like water swirling down a drain, but it’s so hot and moving so fast that it shines brighter than an entire galaxy. This bright flash of X-rays and ultraviolet light is the TDE. It is this sudden, brilliant flare that our telescopes can see from hundreds of millions of light-years away. A TDE is like a flare gun, a black hole’s way of telling us, “Here I am!”

Why Is AT2024tvd Called an “Orphan” Black Hole?

This is the most important part of the story. For decades, when astronomers looked for supermassive black holes, they knew exactly where to point their telescopes: the very center, or nucleus, of a big galaxy. And every time they found a TDE, that bright flash of a star being eaten, it was coming from a galaxy’s center. This confirmed that the giant black holes live “downtown.”

But AT2024tvd broke the rule. This event was spotted in a massive galaxy about 600 million light-years away. But when astronomers used high-powered telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope to pinpoint the flash, they were shocked. The TDE was not in the center. It was offset, about 2,600 light-years away from the galaxy’s core. In cosmic terms, that’s in the middle of the “suburbs,” not the central city.

This makes the black hole an “orphan” or a “wandering” black hole. It’s a giant, massive object that is not anchored to the center of its galaxy. What’s even more fascinating is that this particular galaxy already has a giant black hole in its center. Scientists looked and found the main supermassive black hole, which is a monster weighing about 100 million times the mass of our sun. The orphan black hole that caused AT2024tvd is smaller, estimated to be about 1 million times the mass of our sun. This means this one galaxy has two massive black holes, with one roaming freely. This is the clearest evidence we have ever found that these wandering black holes are real.

How Can a Massive Black Hole Become a Wanderer?

If black holes are supposed to be in the center, how does one end up in the suburbs? Scientists have two main theories, and both are full of cosmic drama. The most popular idea is that this is the leftover of a galaxy merger. Galaxies are not static; they move, and sometimes they crash into each other. Over millions of years, two galaxies can merge to become one, larger galaxy.

When this happens, each galaxy brings its own central supermassive black hole to the party. The new, larger galaxy now has two giant black holes. They will orbit each other, getting closer and closer, and will eventually merge into one even bigger black hole. But what if one galaxy was much larger than the other? The smaller galaxy’s black hole might get tossed around by the complex gravity. It might survive the merger but be thrown into a new, looping orbit around the main galaxy. It becomes a wanderer, the “orphan” core of a galaxy that was eaten long ago. The black hole from AT2024tvd, at one million solar masses, is the perfect size to have been the center of a smaller galaxy that merged with this larger one.

The second theory is even more chaotic. It’s called a three-body interaction. It’s possible that the galaxy’s center used to have two or even three massive black holes swirling around each other. In this gravitational dance, things are very unstable. Eventually, the math works out that one of the black holes gets “kicked” out. Like a slingshot, the gravity of the other two can fling the third one completely out of the center and into a wide, strange orbit in the galaxy’s outer regions. Either way, AT2024tvd is the “smoking gun” that proves these dramatic events happen, leaving massive black holes adrift in the dark.

How Did Scientists Discover AT2024tvd?

Finding a TDE is a needle in a haystack, and it requires a team of telescopes working together. The story of AT2024tvd began at the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) in California. The ZTF is a special robotic telescope that scans the entire northern sky every two nights. It’s not looking for tiny details; it’s looking for changes. Its software compares pictures of the sky from night to night, looking for any new dot of light that appears (a “transient”) or any dot that suddenly gets brighter.

In early 2024, ZTF’s computers flagged a new, bright flash in a galaxy 600 million light-years away. This flash got an automatic name: AT2024tvd (which stands for Astrophysical Transient 2024 tvd). An alert was sent out to astronomers all over the world. This is where the detective team comes in. Scientists immediately pointed other, more powerful telescopes at this new flash to figure out what it was.

They used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which can see in ultraviolet (UV) light and has incredibly sharp vision. Hubble’s UV images are what confirmed the flash was not in the center of the galaxy. They also used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. A TDE is one of the few things in the universe hot enough to glow brightly in X-rays, and Chandra saw that X-ray glow, confirming it was a black hole feeding. Finally, radio telescopes like the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico listened in and heard powerful radio signals, which is the “static” from the high-speed gas being thrown out by the event. By combining all this data, the team pieced together the full story: an offset, wandering black hole was eating a star.

What Kind of Black Hole Is This?

The black hole behind AT2024tvd is estimated to be about one million times the mass of our sun. This is fascinating because it places it in a very special category. As we discussed, we see small “stellar” black holes (a few times our sun’s mass) and “supermassive” ones (many millions to billions). But what about the ones in between?

Scientists have long searched for Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs). These are the “missing link” black holes, weighing from a few hundred to a few hundred thousand times the mass of our sun. We call them the “teenagers” of the black hole world, and they are incredibly hard to find. We are not sure how they form or where they live. They are too small to be the anchors of big galaxies, but they are too big to be formed from a single star.

While the one million solar mass black hole of AT2024tvd is just on the low end of being “supermassive,” it is a perfect candidate for showing us how IMBHs grow. One theory is that these intermediate black holes are the “seeds” that eventually grow into the supermassive ones. A million-solar-mass black hole is exactly the size we would expect to find at the center of a small dwarf galaxy. If the galaxy merger theory is correct, AT2024tvd is not just a wandering black hole; it’s a captured IMBH or a small supermassive black hole that proves our theory about how galaxies and their black holes grow by eating smaller ones. Finding this object is a major step in understanding the complete life cycle of black holes.

What Does This Discovery Tell Us About the Universe?

This discovery changes how we search for black holes. For a long time, we have been “looking under the lamppost.” We searched for TDEs only in the bright centers of galaxies because that’s where we knew the light was. We were finding the “house cats.” But AT2024tvd proves that there is a hidden population of “stray” or “feral” massive black holes, and that they also hunt.

This means there could be thousands of these wandering black holes in a big galaxy like our own Milky Way, all left over from ancient mergers. They are completely dark and invisible, so we would never know they are there. But every 100,000 years or so, one of them might get lucky and snatch a passing star. When it does, it lights up with a TDE flare.

By finding AT2024tvd, scientists have learned what to look for. They can now scan the “empty” parts of galaxies, not just the centers, for these sudden flashes. This single event opens up a whole new field of astronomy. It allows us to take a “census” of these hidden wanderers. By counting them, we can learn how many mergers our galaxy has had in the past and build a much more complete picture of how galaxies are built over billions of years. This orphan black hole is a single clue, but it points to a vast, hidden population of objects we had only dreamed of finding.

Conclusion

The discovery of AT2024tvd is far more than just a spectacular cosmic explosion. It is a flash of light that has illuminated a dark mystery. By catching this “orphan” black hole in the act of eating a star, scientists have found the clearest proof yet that massive black holes can and do wander far from their galactic homes. This single event, first spotted by a robotic telescope and then confirmed by a team of world-class observatories, has given us a new tool to find this hidden population.

This event was likely caused by a dramatic galactic merger long ago, which left the black hole of a smaller, swallowed galaxy to roam through its new, larger home. AT2024tvd is the first of its kind found this way, but it certainly will not be the last. We are now entering a new era of astronomy where we are no longer just looking for the giants in their palaces, but for the wanderers in the dark. It makes you wonder, if a one-million-sun black hole can be hiding in the suburbs of a galaxy, what other “invisible” giants are still out there waiting to be discovered?

FAQs – People Also Ask

What does AT2024tvd stand for?

The name is a scientific label. “AT” stands for “Astrophysical Transient,” which is a general name for any new flash of light in space. “2024” is the year it was discovered. And “tvd” is a unique set of letters assigned automatically, like a license plate, to tell it apart from other events found that year.

Is an orphan black hole dangerous to Earth?

No, this black hole is not dangerous to us. AT2024tvd is in a completely different galaxy, about 600 million light-years away from Earth. It is incredibly far away. Even if there are wandering black holes in our own Milky Way, space is so unbelievably vast that the chances of one coming anywhere near our solar system are practically zero.

How long does a tidal disruption event last?

A TDE is a long event. The actual “spaghettification” process of the star being torn apart can happen very quickly, in just a matter of hours. However, the bright flare we see, which comes from the star’s material heating up in the accretion disk, can last for a very long time. It can brighten over several weeks and then slowly fade away over many months or even years.

What is the difference between a supernova and a TDE?

Both are huge explosions in space, but they have different causes and “fingerprints.” A supernova is the death of a single, massive star, or the explosion of a white dwarf. A Tidal Disruption Event (TDE) is the death of a star that is caused by an external object: a black hole. Scientists can tell them apart by studying their light: TDEs are often bluer, hotter, and glow very brightly in X-ray and ultraviolet light, which is different from most supernovae.

Why are intermediate-mass black holes so hard to find?

Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs) are hard to find because they are invisible and they don’t have a clear “home.” Stellar-mass black holes are found all over the galaxy, and supermassive ones are always at the bright center. IMBHs are thought to be in places like the centers of small dwarf galaxies or in dense clusters of stars, which are harder to study. We can only find them when they are actively eating something, which is very rare.

How many wandering black holes are in our galaxy?

Scientists are not sure, but this discovery suggests there could be many. Some models predict there could be hundreds or even thousands of wandering black holes in a large galaxy like our Milky Way. Most of these would be leftovers from all the smaller galaxies that the Milky Way has merged with over the last 13 billion years.

What is spaghettification?

Spaghettification is the real, scientific term for what happens when an object gets too close to a strong gravitational source, like a black hole. The gravity on the part of the object closer to the black hole is so much stronger than the gravity on the part farther away that the object is stretched vertically, like a piece of spaghetti, while being squeezed in from the sides.

Could our sun be eaten by a black hole?

It is extremely unlikely. Our solar system is in a safe and stable orbit in the suburbs of the Milky Way, far from the supermassive black hole at the center (Sagittarius A*). There are no known black holes close enough to us to be a danger. For our sun to be eaten, a wandering black hole would have to pass perfectly through our small solar system, an event that is statistically almost impossible.

How far away is AT2024tvd?

The event AT2024tvd took place in a massive galaxy that is about 600 million light-years away from Earth. This means the light from this star being torn apart traveled for 600 million years through space before it finally reached our telescopes.

What telescope found AT2024tvd?

The event was first detected by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), which is an automated sky survey in California. After ZTF flagged the new bright spot, a team of other telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, were used to study it in detail, confirm what it was, and pinpoint its exact location.

This video from YouTube discusses a tidal disruption event, which is the same type of cosmic event as AT2024tvd, where a star is torn apart by a black hole.