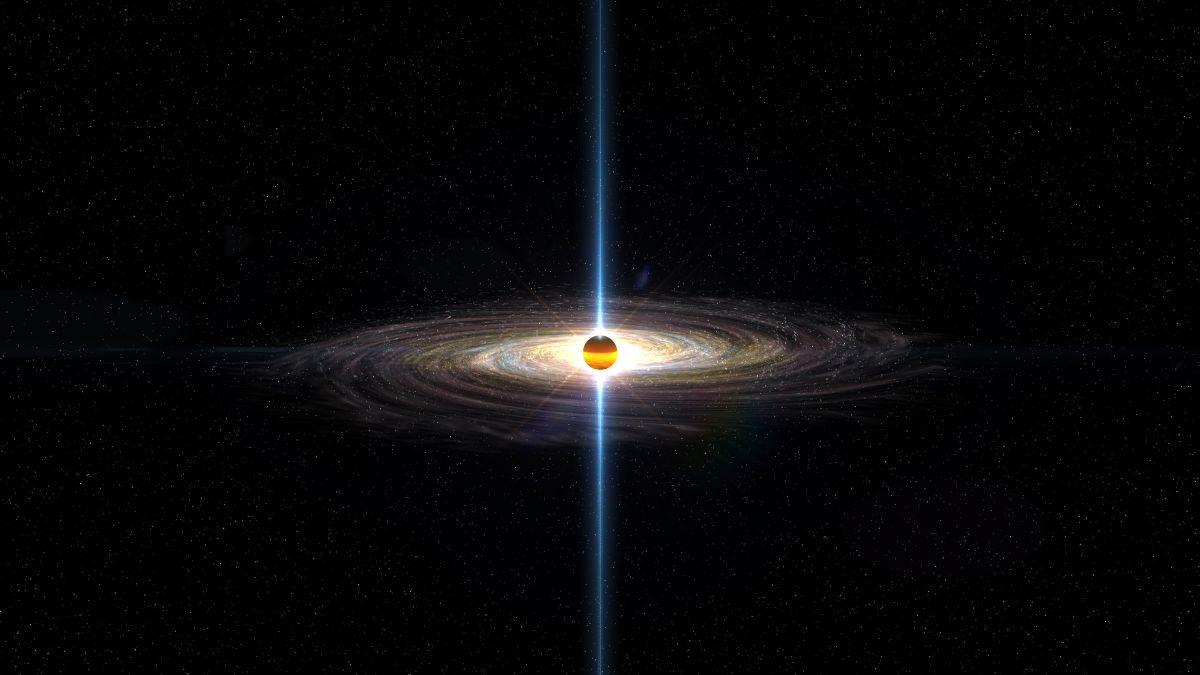

The universe is a place of incredible scale and power, filled with events so extreme they challenge our understanding of physics. We often think of space as quiet and empty, but it hosts some of the most violent and energetic processes imaginable. At the heart of most large galaxies, including our own Milky Way, lurks a supermassive black hole—an object with the mass of millions or even billions of suns, packed into a tiny point of infinite density. These cosmic giants are the gravitational anchors of their galaxies, shaping the stars and systems that orbit them.

Galaxies themselves are not isolated islands in space. They move, interact, and sometimes, over billions of years, they collide and merge. When two galaxies combine, their central supermassive black holes begin a slow, cosmic dance. They are pulled toward the center of the new, larger galaxy, where they start to orbit each other. For millions of years, they spiral closer and closer, locked in a gravitational embrace that can only end in one way: a cataclysmic merger. This event is one of the most powerful in the entire universe, releasing more energy in a few moments than all the stars in the cosmos combined.

While these collisions happen in distant galaxies all the time, they are too far away for us to see in great detail. But this raises a fascinating question about what we would witness if such a monumental event happened much closer to home. What would we actually experience if two of these cosmic titans finally came together in our cosmic neighborhood?

What exactly is a supermassive black hole?

Before diving into a collision, it is helpful to understand just how different a supermassive black hole is from a regular one. When a giant star dies, it can collapse under its own gravity to form what is called a stellar-mass black hole. These are relatively common, but they typically only have a mass a few times greater than our Sun. A supermassive black hole, or SMBH, is a completely different kind of beast. These are the largest type of black hole, with masses ranging from millions to tens of billions of times the mass of our Sun. They are so enormous that if one were placed at the center of our solar system, its edge might extend beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

These giants are found at the core of almost every large galaxy. Our own Milky Way has one called Sagittarius A*, which has a mass of about four million suns. While that sounds huge, it is quite modest compared to others. The black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87, which was famously imaged in 2019, has a mass of over six billion suns. Scientists believe these SMBHs grew to their immense size over billions of years. They may have started as smaller black holes that gradually consumed vast amounts of gas, dust, and stars. They also grew by merging with other black holes during galactic collisions, a process that continues across the universe today.

Think of an SMBH as the gravitational heart of its galaxy. Its immense pull helps to hold the galaxy together and influences the orbits of stars in the central region. While its gravity is powerful, it does not “suck up” everything around it like a vacuum cleaner. Stars and planets can orbit a black hole safely for billions of years, just as we orbit the Sun. The danger only arises if an object’s path takes it too close to the event horizon—the point of no return from which not even light can escape.

How could two supermassive black holes get close enough to collide?

The journey toward a supermassive black hole collision is an incredibly long and slow process that begins with the merging of two entire galaxies. Galaxies are constantly in motion, pulled by the gravity of their neighbors and the underlying structure of the universe. When two galaxies get close enough, their mutual gravity can pull them into a collision course. This is not a quick crash like a car accident. Because galaxies are mostly empty space, they typically pass through each other. However, their gravitational forces interact dramatically, pulling out long streams of stars and gas and disrupting their neat spiral shapes.

After the initial pass, gravity pulls them back together, and they continue to interact over hundreds of millions of years. During this time, they gradually lose momentum and merge into a single, larger, and often more chaotically shaped galaxy. As this happens, the two supermassive black holes that once sat at the centers of the original galaxies begin their own journey. Pulled by gravity, they sink toward the core of the newly formed galaxy. Eventually, they become gravitationally bound to each other, forming a binary system where two supermassive black holes orbit a common center of gravity.

Even at this stage, the merger is far from over. At first, the two black holes are separated by many light-years, and their orbit is slow. They continue to clear out stars and gas from the galactic center, a process that causes them to lose orbital energy and spiral even closer together. This dance can last for an incredibly long time. In the final phase of their journey, as they get extremely close, another force takes over. They begin to stir the very fabric of spacetime, creating powerful ripples known as gravitational waves. These waves carry away huge amounts of energy, causing the black holes to spiral inward faster and faster until they finally merge.

What happens in the final moments before they merge?

The final moments of a supermassive black hole merger are the most violent and energetic part of the entire process. As the two giants spiral closer, their orbital speed increases to a significant fraction of the speed of light. They might be whipping around each other hundreds of times per second just before they touch. In this frantic dance, their immense gravitational fields warp spacetime so intensely that they create a storm of gravitational waves. These ripples in the fabric of the universe travel outward at the speed of light, carrying away an astonishing amount of energy.

Scientists who study these events describe the gravitational wave signal as a “chirp.” As the black holes get closer and faster, the frequency and amplitude of the waves they produce increase rapidly. This is the sound of spacetime itself being twisted and squeezed by the immense, accelerating masses. In the final fraction of a second, the energy released through these gravitational waves is more than the energy produced by all the stars in the observable universe combined. It is a truly mind-boggling amount of power, all generated by the conversion of mass into pure energy, as described by Einstein’s famous equation, $E=mc^2$.

Surrounding the black holes, any remaining gas and dust from their accretion disks—rings of material swirling around them—would be heated to millions of degrees. The collision of these disks would create a brilliant flash of light across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to powerful X-rays and gamma rays. This burst of light could be so bright that it would temporarily outshine the entire host galaxy. For any observers in a distant galaxy, this brilliant flare would be the first visible sign that a monumental cosmic event was taking place.

What would we see and feel if the collision happened nearby?

If a merger of two supermassive black holes happened in a “nearby” galaxy, such as Andromeda, which is about 2.5 million light-years away, the effects on Earth would be detectable but not dangerous. We would not see the black holes themselves, but we would witness the spectacular aftermath. The first thing we would notice is the brilliant flash of light. Telescopes around the world would detect a new, incredibly bright point of light in the sky, a beacon announcing the merger. This light, a result of the colliding accretion disks, would be visible for weeks or months before fading away. It would be a major astronomical event, studied by scientists to understand the extreme physics at play.

At the same time this light reaches us, the gravitational waves from the merger would also wash over the Earth. It is important to understand that we would not physically feel them. These waves stretch and compress the fabric of spacetime itself, but the effect is unimaginably small by the time it reaches us. The change in distance between two points on Earth would be less than the width of a proton. We would have no personal sensation of this happening at all.

However, our most sensitive scientific instruments would certainly detect it. Gravitational wave observatories like LIGO in the United States and Virgo in Italy are designed for this exact purpose. They use powerful lasers bounced between mirrors in long, L-shaped tunnels. As a gravitational wave passes, it slightly stretches one arm of the detector while compressing the other. This tiny change is enough to create a clear signal, the “chirp” that confirms the merger. Detecting these waves from a supermassive black hole merger would be a landmark achievement, giving us a completely new way to observe the universe’s most extreme events.

What are the biggest dangers from such a cosmic event?

For an event this powerful, it is natural to wonder about the potential dangers. Fortunately, if a merger happens in another galaxy, even a nearby one, there is no direct threat to Earth. The gravitational waves are too faint to affect us physically, and the light and radiation are too far away to cause any harm. The real danger would only come into play if a merger happened much closer—specifically, within our own Milky Way galaxy, and if the event’s high-energy jets were pointed directly at us. The probability of this is practically zero, as our galaxy’s central black hole is not currently on a merger course with another SMBH.

If such an unlikely event were to occur, the primary danger would not be from gravity but from radiation. The collision could produce powerful jets of high-energy particles and gamma rays. If Earth were in the direct path of one of these jets, the blast of radiation could be strong enough to strip away our planet’s ozone layer, leaving us exposed to harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. This would be a catastrophic extinction-level event. Again, the chances of a merger happening this close and being aimed perfectly at us are so small that it is not something astronomers worry about.

Another interesting and potentially disruptive outcome of a merger is the “gravitational kick.” When two black holes of different sizes or spins merge, the gravitational waves are not emitted perfectly evenly in all directions. This imbalance creates a recoil effect, much like the kick from a rifle. The newly formed, single black hole can be “kicked” in one direction at incredible speeds, potentially up to millions of miles per hour. This speed could be high enough to eject the new black hole from its host galaxy entirely, sending it hurtling through intergalactic space as a rogue supermassive black hole.

What is left behind after the two black holes merge?

The immediate result of the collision is the birth of a single, more massive black hole. However, the final mass is not simply the sum of the two original masses. During the final moments of the merger, a significant amount of their mass—equivalent to several entire suns—is converted directly into energy in the form of gravitational waves. This is the source of the incredible power released during the event. The new black hole that remains is therefore slightly less massive than the two initial black holes combined, with the missing mass radiated away as gravitational energy.

Immediately after the merger, the new black hole is not perfectly stable. The collision creates a single, distorted event horizon that is wobbling and vibrating, much like a bell that has just been struck. This phase is known as the “ringdown.” To settle into its final, stable, spherical shape, the black hole sheds the last of its distortions by emitting more gravitational waves. These waves are like the fading tones of the ringing bell. The specific frequencies of the ringdown waves are very important to scientists because they contain precise information about the final black hole’s mass and spin.

By studying the ringdown signal, physicists can test Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity in the most extreme gravitational environment known to exist. The theory makes very precise predictions about what this signal should look like. So far, all the gravitational waves detected from smaller black hole mergers have perfectly matched these predictions, confirming that our understanding of gravity holds up even under these incredible conditions. The new, settled black hole will then continue its life as the anchor of its galaxy, quietly waiting for its next meal of gas, dust, or an unlucky star that wanders too close.

How do scientists actually search for these events?

Searching for supermassive black hole mergers requires a combination of different astronomical techniques, a field known as multi-messenger astronomy. Because these events produce both light and gravitational waves, scientists use different kinds of observatories to get a complete picture. The primary tool for detecting the merger itself is a gravitational wave observatory. Ground-based detectors like LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA are excellent at finding the high-frequency “chirps” from the mergers of smaller, stellar-mass black holes. However, the waves from giant supermassive black holes are of a much lower frequency, requiring different methods to detect.

To find these low-frequency waves from SMBHs that are still millions of years away from merging, astronomers use a technique called a Pulsar Timing Array. This involves carefully monitoring dozens of pulsars—highly stable, spinning neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves like a lighthouse. These pulses arrive on Earth with incredible regularity. If a low-frequency gravitational wave from a distant SMBH binary passes through our galaxy, it subtly stretches and squeezes the space between us and the pulsar, causing a tiny, predictable delay in the arrival time of the pulses. In 2023, collaborations like NANOGrav announced strong evidence of this background hum of gravitational waves, suggesting a universe filled with these orbiting giant black holes.

At the same time, traditional telescopes search for the electromagnetic signals—the light—from these events. When astronomers suspect a merger might be happening, they can point telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope toward the galaxy to look for the characteristic flare of light from the colliding accretion disks. By combining the data from gravitational waves and light, scientists can learn far more than they could from either one alone. This powerful combination allows them to pinpoint where the event happened, how massive the black holes were, and what their environment was like.

Conclusion

The collision of two supermassive black holes is a truly awesome display of nature’s power. It is a process that unfolds over cosmic timescales, beginning with the slow dance of galaxies and ending in a final, violent burst of energy that shakes the very fabric of spacetime. The light from this event can outshine a galaxy, while the gravitational waves carry away the energy of billions of suns. What is left behind is a new, larger black hole, a silent monument to the cosmic union that created it.

For us on Earth, these events pose no direct threat. They happen so far away that their power is diluted by distance, becoming faint whispers detectable only by our most advanced instruments. Yet, these whispers tell us a profound story about the life cycle of galaxies and the fundamental laws of the universe. They offer a unique window into the extreme physics of gravity, allowing us to test our theories in a cosmic laboratory we could never hope to replicate. As our technology for listening to the universe improves, what other secrets will the echoes of these cosmic collisions reveal?

FAQs – People Also Ask

Could a black hole collision destroy the Earth?

No, a black hole collision in another galaxy could not destroy the Earth. The gravitational waves are too weak by the time they reach us to cause any physical damage, and the radiation is too far away. The only hypothetical danger would be from a merger inside our own galaxy aimed directly at us, which is an extremely unlikely scenario.

How often do supermassive black holes collide?

While it is a rare event in any single galaxy, astronomers believe that supermassive black hole collisions happen fairly regularly across the vastness of the universe. Current models suggest that in the observable universe, a merger event might be happening every few years, but detecting them is still a major scientific challenge.

What is the sound of two black holes merging?

There is no sound in space because sound requires a medium like air to travel. However, scientists can convert the gravitational wave signals into sound waves. The signal, known as a “chirp,” starts as a low rumble that rapidly rises in frequency and volume, ending in a final “pop” as the two black holes merge into one.

Has NASA ever seen two black holes collide?

NASA, along with international partners operating observatories like LIGO and Virgo, has detected the gravitational waves from dozens of collisions between smaller, stellar-mass black holes. While we have not yet directly confirmed the final merger of two supermassive black holes, we have observed many pairs of them orbiting each other in distant galaxies, on a path to a future collision.

What is the largest black hole ever discovered?

One of the largest known black holes is TON 618, which has an estimated mass of 66 billion times that of our Sun. It is so massive that it powers an incredibly bright quasar, an active galactic nucleus that outshines its entire host galaxy. Black holes of this scale are exceptionally rare.

Could our own galaxy’s black hole collide with another?

Yes, it is expected to happen in the distant future. The Milky Way is on a collision course with the Andromeda galaxy, and they are predicted to merge in about 4.5 billion years. Eventually, our central black hole, Sagittarius A*, will merge with Andromeda’s central black hole to form a new, even larger one.

What are gravitational waves?

Gravitational waves are ripples or disturbances in the fabric of spacetime, created by the acceleration of massive objects. They were first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 and directly detected for the first time in 2015. They are a fundamentally new way to observe the universe, separate from light.

How fast do gravitational waves travel?

Gravitational waves travel at the speed of light. This was confirmed in 2017 when scientists detected gravitational waves and a flash of light from the same event—a merger of two neutron stars—and both signals arrived at Earth at virtually the same time after traveling for 130 million years.

What happens to the stars around merging black holes?

In the early stages of the merger, many stars in the galactic core are ejected by the gravitational interactions of the two orbiting black holes, a process called gravitational slingshot. Any stars that remain too close to the final merger event would likely be consumed or torn apart by the extreme tidal forces.

Is there a black hole in the center of every galaxy?

Scientists believe that nearly all large galaxies, including our own, have a supermassive black hole at their center. However, some smaller dwarf galaxies do not appear to have one. The relationship between the growth of a galaxy and its central black hole is a very active and important area of astronomical research.