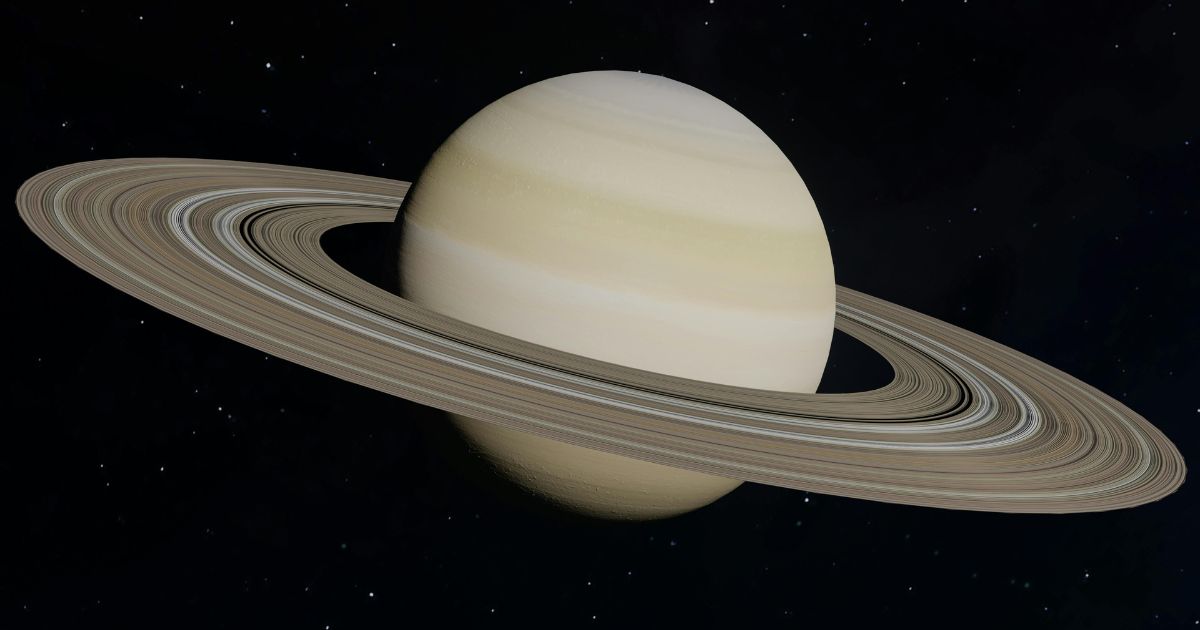

Saturn is famous for one big reason: its beautiful, stunning rings. They are like a giant, flat halo made of ice and rock orbiting the planet. For centuries, they have been a symbol of the wonders of space. But you may have heard some news that sounds alarming. Headlines say that Saturn’s rings are disappearing, and some even point to the year 2025. This news is true, but it’s actually two different stories happening at the same time. One is a temporary illusion, and the other is a very real, very slow end to the most beautiful feature in our solar system.

One “disappearance” is happening very soon, in 2025. This is a temporary event that has nothing to do with the rings being destroyed. It is a simple, repeating trick of perspective, like a magic illusion happening in the sky. It happens every 15 years or so, and it even confused the first astronomers who saw it. This event is a fantastic opportunity for scientists, but it is not a disaster. It is a normal part of how the planets orbit the sun.

The second “disappearance” is the much bigger story. This one is real, permanent, and is happening right now, every single second. Saturn is slowly, but surely, destroying its own magnificent rings. Its gravity is pulling the rings in, particle by particle, in a process that scientists have only recently been able to measure. This discovery has changed everything we thought we knew about Saturn, telling us the rings are much younger and more temporary than we ever imagined. So what is really going on with Saturn, and how do we know all of this?

What Is Happening to Saturn’s Rings in 2025?

You can relax about the news for 2025. Saturn’s rings are not being destroyed or vanishing forever next year. What is happening is an amazing event called a “ring plane crossing.” This is an optical illusion from our point of view here on Earth. On March 23, 2025, Saturn will be tilted in such a way that we see its rings perfectly edge on. Because the rings are incredibly thin, they will seem to vanish completely when viewed through most telescopes. It is like holding a giant sheet of paper in front of you. If you look at it flat, it is huge. But if you turn it so only the thin edge is facing you, it becomes a tiny, almost invisible line.

This illusion happens because planets are tilted. Earth is tilted on its axis by 23.5 degrees, which is what gives us our seasons. Saturn is also tilted, by about 26.7 degrees. As Saturn makes its long, 29.4 year journey around the sun, our view of this tilt changes. Sometimes, we see the top of the rings, making them look wide and bright. At other times, we see the bottom. But twice during its orbit, about every 13 to 15 years, Earth passes through the “ring plane.” This is the flat level that the rings orbit on. During this crossing, we see them from the side, and they disappear.

The only reason this illusion is so dramatic is because of how thin the rings really are. While the main ring system stretches over 175,000 miles (282,000 kilometers) from end to end, its vertical thickness is tiny. In most places, the rings are only about 30 feet (10 meters) to 330 feet (100 meters) thick. That is astoundingly thin. If you built a scale model of the rings that was the size of a football field, the rings themselves would be thinner than a single sheet of paper. This is why, when they turn sideways to us, they become invisible.

This is not a new discovery. In fact, it is one of the oldest mysteries of Saturn. When the astronomer Galileo Galilei first looked at Saturn with his new telescope in 1610, he did not see rings. His telescope was not good enough, so he saw what he thought were two large “ears” or “moons” on either side of the planet. He was baffled when he looked again in 1612 and they were gone. He had no idea where they went. It was not until 1655 that the astronomer Christiaan Huygens, with a better telescope, correctly figured out that Saturn was surrounded by a “thin, flat ring” that was not attached to it. What Galileo saw in 1612 was the first recorded observation of a ring plane crossing. The last one happened in 2009, and after the 2025 event, the next one will be in 2038.

Are Saturn’s Rings Actually Disappearing Forever?

Yes. This is the second, much more serious story. While the 2025 event is a temporary illusion, the rings are, in fact, permanently disappearing. This is a real, physical process. The rings are not stable. They are in a slow, cosmic battle with Saturn’s gravity, and they are losing. Scientists, using data from NASA’s space missions, have confirmed that the rings are being torn apart and are “raining” down onto the planet. This process is happening right now, as you read this.

So when will they be gone? Not in our lifetimes, or even our great grandchildren’s lifetimes. The most current estimates, based on the latest data, suggest the rings have about 100 million years left. Some models show they could last as long as 300 million years. This sounds like an incredibly long time, and for a human, it is. But in cosmic terms, it is a blink of an eye. The planet Saturn, along with the rest of our solar system, is about 4.5 billion years old. If the rings will only last for another 100 million years, it means they are a very temporary feature.

This discovery has led to a stunning conclusion: we are alive at a very special time. We are living in the “golden age” of Saturn. It is very likely that for most of its 4.5 billion year history, Saturn had no rings. It is also very likely that in the distant future, it will have no rings again. We just happen to be the lucky species that evolved during the brief, 100 or 200 million year window when Saturn has this spectacular decoration. Dinosaurs, for example, probably looked up at a Saturn that had no rings at all. This makes the rings feel even more precious and special. They are not a permanent part of our solar system, but a beautiful, fleeting show.

What Is “Ring Rain” and How Is It Destroying the Rings?

The scientific term for the rings’ destruction is “ring rain.” It is exactly what it sounds like: a constant, invisible shower of particles from the rings falling down onto Saturn’s atmosphere. This is the main culprit behind the rings’ permanent disappearance. It is a downpour of ice and dust, pulled from the rings by gravity and the planet’s powerful magnetic field. This rain is happening 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and has been for millions of years.

The process works in a few ways. First, there is the simple pull of Saturn’s gravity. The rings are in a constant tug of war. Their orbital speed, or velocity, wants to fling them out into space. Saturn’s gravity wants to pull them down to the surface. For the main, bright rings, these forces are mostly in balance. But for the innermost, faintest rings, gravity is slowly winning. It steadily pulls particles out of orbit and down toward the planet.

But gravity is not the only force at work. Saturn’s magnetic field plays a huge role. The tiny ice particles in the rings are constantly bombarded by two things: ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun, and tiny meteoroids, which are microscopic bits of space dust. These impacts and radiation can knock electrons off the ice particles, giving them a tiny electrical charge. Once a particle is charged, it is no longer just controlled by gravity. It can now be grabbed by Saturn’s giant magnetic field. This magnetic field, which is thousands of times stronger than Earth’s, funnels these charged particles along invisible lines, directing them down into the planet’s upper atmosphere, especially near the equator.

This is not a slow, gentle “drizzle.” Data from NASA’s missions showed that it is a “downpour.” Scientists were able to calculate the rate at which this ring rain is falling. The numbers are staggering. Every single second, about 22,000 pounds (10,000 kilograms) of ring material is being dumped onto Saturn. That is the weight of a large truck, or a school bus, of ice and dust, every second. NASA scientists have said this is enough water to fill an Olympic sized swimming pool every half an hour. When you realize that this much material is being lost every day, for millions of years, you can understand why the rings will not last forever. This massive rate of loss is what allowed scientists to calculate their short, 100 million year lifespan.

How Did Scientists Discover the Rings Were Disappearing?

This entire discovery is a fantastic piece of scientific detective work that took decades and involved multiple space missions. The very first clues came in the 1980s when NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by Saturn. They noticed strange, dark bands in Saturn’s upper atmosphere and saw signs that material from the rings was interacting with the planet. The idea of “ring rain” was born, but it was just a theory. There was no way to prove it or, more importantly, to measure it.

The real proof, the “smoking gun,” came from the Cassini mission. This robotic spacecraft, a joint project between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Italian Space Agency (ASI), orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017. For 13 years, it gave us the most detailed look at the planet and its rings we have ever had. But the most incredible science came at the very end of its life, in a daring maneuver called the “Grand Finale.”

In 2017, the Cassini spacecraft was running out of fuel. Instead of letting it crash into a moon like Enceladus, which might have life, scientists sent it on a final, heroic journey. They programmed Cassini to perform 22 orbits that would take it where no spacecraft had ever gone before: into the 1,200 mile (2,000 kilometer) wide gap between Saturn’s cloud tops and its innermost D ring. This was an incredible risk. If it hit even a small piece of ring material, the spacecraft would be destroyed. But it worked.

As Cassini dove through this gap, it was, for the first time, inside the ring rain. It was no longer just looking at the rings; it was flying right through the particles that were falling onto the planet. Its instruments could “taste” and “smell” this rain. An instrument called the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) was designed to study gases, but it was pelted by ring particles. These particles vaporized on impact, allowing the instrument to measure exactly what they were made of. Scientists were stunned. They found exactly what they expected: water. But they also found things they did not expect, like methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, and complex organic molecules like butane and propane. The rings were not just pure water ice; they were a complex chemical soup.

The Grand Finale did one other crucial thing. By flying inside the rings, Cassini allowed scientists to “weigh” the rings for the first time. Before this, when Cassini was outside the rings, it was being pulled by the gravity of both Saturn and the rings. It was hard to tell their masses apart. But once it was inside the rings, it could feel the pull of the planet separately from the pull of the rings. This new data allowed scientists to calculate the rings’ total mass. The answer was, again, a shock. The rings were much “lighter” or less massive than most models had predicted.

This was the final piece of the puzzle. Scientists now had the two most important numbers. They knew the mass of the rings (they are light) and the rate of loss from the ring rain (it is very high, at 22,000 pounds per second). With these two facts, it was simple math. A light set of rings losing material at such a high rate means they cannot last long. This is how scientists confidently concluded that the rings are young and have only about 100 million years left before they are completely gone.

What Are Saturn’s Rings Made Of?

It is easy to think of the rings as solid, flat discs, like a vinyl record. But they are not solid at all. If you could fly a spaceship through them, you would see that they are made of billions, maybe trillions, of individual, separate pieces of ice and rock. These pieces are all orbiting Saturn together, like a giant, crowded highway. The main rings, the ones we see clearly, are made almost entirely of water ice. More than 99% of the material is frozen water.

The “ice cubes” that make up the rings come in all different sizes. Some are microscopic, as small as a grain of dust or smoke. Others are the size of pebbles or small rocks. Many are the size of a car, and some are as large as a house or even a small mountain. All of these pieces, from dust to boulders, are orbiting Saturn at incredibly high speeds, over 45,000 miles per hour (72,000 kilometers per hour). This is why the Grand Finale was so dangerous; hitting even a small pebble at that speed would be catastrophic.

The rings are also not just one big system. They are a complex collection of many different rings and gaps. Scientists have named the main rings with letters of the alphabet, in the order they were discovered. Starting from the planet and moving outward, the main rings are named D, C, B, and A. Then, outside the main rings, are the F, G, and E rings. The D ring is the innermost and faintest, and it is the one that is primarily responsible for the “ring rain.” The B ring is the largest and brightest. The famous gap between the A and B rings is called the “Cassini Division,” named after the astronomer who discovered it.

The small amount of “dirt” or rocky material in the rings is actually a very important clue. For billions of years, space has been full of tiny micrometeoroids. If the rings were 4.5 billion years old, like the planet, they should be “dirty.” They should be coated in a thick layer of dark, rocky dust from all these billions of years of impacts. But they are not. The Cassini mission confirmed that the rings are bright and surprisingly “clean.” They are mostly pure, sparkling ice. This tells scientists that the rings cannot be old. They must be young.

Why Does Saturn Have Rings in the First Place?

This is the biggest mystery that the Cassini mission helped solve. For a long time, there were two main theories. One theory said the rings were “primordial,” meaning they formed at the same time as Saturn, 4.5 billion years ago, from the original disk of gas and dust that formed our solar system. The second theory said the rings were “recent,” meaning they were created much later.

The evidence from Cassini has almost completely settled this debate. The rings are young. They are not 4.5 billion years old. The data—their low mass, their clean and icy composition, and the high rate of ring rain—all point to the rings being a recent addition. The best estimates suggest the rings are only between 10 million and 100 million years old. This is incredibly young. When the rings of Saturn were born, dinosaurs were already roaming the Earth, and some may have even been extinct.

So, if the rings are new, where did they come from? The leading theory is that they are the shattered, gory remains of a large, icy moon. It is a story of cosmic violence. This theory suggests that 100 million years ago, Saturn had at least one more large moon than it does today. This icy moon, which scientists have nicknamed “Chrysalis,” was orbiting the planet peacefully. But something happened—perhaps its orbit was destabilized by the pull of other moons—and it began to spiral inward, closer and closer to Saturn.

This moon was headed for disaster. It was on a collision course with an invisible boundary in space called the Roche limit. The Roche limit is the “danger zone” around a large planet. It is the point where the planet’s gravity is so strong that it becomes a tidal force, pulling harder on the near side of the moon than it does on the far side. Once Chrysalis crossed this line, it was torn apart. The planet’s gravity shredded the entire moon, ripping it to pieces.

Scientists believe that about 99% of this destroyed moon’s mass fell straight into Saturn. But the other 1%, the icy outer layers, spread out into a disk of trillions of ice chunks. This debris settled into the wide, flat, and beautiful rings we see today. This “Chrysalis” theory is so powerful because it neatly solves two of Saturn’s biggest mysteries at once. First, it explains why the rings are young and icy: they are the fresh, frozen guts of a recently destroyed moon. Second, it explains why Saturn is tilted at 26.7 degrees. Scientists believe the chaotic gravitational event of this moon being torn apart and falling into the planet was so violent that it literally “knocked” Saturn over, giving it its strange tilt.

Does This Mean Other Planets Could Lose Their Rings?

Saturn is not the only planet with rings; it is just the only one with spectacular rings. The other giant planets in our solar system—Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune—all have ring systems of their own. You just cannot see them with a backyard telescope because they are extremely thin, dark, and faint. Unlike Saturn’s bright, icy rings, their rings are made of dark, dusty, rocky material.

The same forces that are destroying Saturn’s rings are at work on these other planets, too. Gravity, sunlight, and magnetic fields are universal. It is very likely that Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune are also slowly “eating” their own rings, and that all ring systems in our solar system are temporary. This has led scientists to believe in a “life cycle” for rings. They are not permanent fixtures. They are born, they live, and they die.

It is possible that billions of years ago, Jupiter or Neptune had a magnificent ring system that we missed, and what we see today are just the faint leftovers. In Saturn’s case, we are seeing a ring system in its “middle age”—bright, full, and in the process of slowly fading away. This process can even happen in the future. We can see a new ring system being born. The small moon of Mars, Phobos, is slowly spiraling inward toward the red planet. In about 50 to 70 million years, it will cross Mars’s Roche limit. When it does, Mars’s gravity will tear it to pieces, and Mars will, for a time, have its own set of rings.

Conclusion

So, are Saturn’s rings disappearing? Yes, in two very different ways. The 2025 event is a wonderful, temporary illusion, a trick of a light and geometry that lets us appreciate just how thin and delicate the rings are. It is a fun event that astronomers have known about for centuries. But the real, permanent disappearance is a far grander story. We have learned that the rings are not an ancient, eternal feature, but a young and temporary marvel.

Thanks to the incredible journey of the Cassini spacecraft, we know that Saturn is actively destroying its own rings. A “downpour” of ice, 22,000 pounds per second, is raining down on the planet, guaranteeing that in 100 million years, the rings will be nothing but a memory. This discovery is a powerful reminder that the universe is not static; it is a place of constant, dynamic change, of creation and destruction. We are just incredibly lucky to be here to see Saturn in its full glory.

If Saturn’s rings are so new and temporary, what other amazing, fleeting sights might our solar system create in the millions of years to come?

FAQs – People Also Ask

Will Saturn’s rings really be gone in 2025?

No, the rings are not permanently vanishing in 2025. This is a temporary optical illusion called a “ring plane crossing.” Because Earth will be viewing the rings perfectly edge on, their incredibly thin profile will make them invisible to most telescopes for a few months before they reappear.

Why are Saturn’s rings so thin?

While the rings are over 175,000 miles wide, they are only about 30 to 330 feet thick in most places. This extreme thinness is a result of gravity and collisions. Over millions of years, any particles that were in tilted or “fluffy” orbits would have collided with other particles, canceling out their vertical motion and forcing the entire system to flatten into the thinnest possible disk.

What mission discovered Saturn’s ring rain?

The NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini mission discovered and measured the ring rain. During its “Grand Finale” in 2017, the spacecraft flew into the gap between the planet and the rings, where its instruments were able to directly sample the particles of ice and organic compounds as they fell into Saturn’s atmosphere.

How fast are Saturn’s rings disappearing?

Scientists estimate that Saturn is losing about 22,000 pounds (10,000 kilograms) of ring material every single second. This “ring rain” is so heavy that it could fill an Olympic sized swimming pool with water every 30 minutes. This high rate of loss is why the rings are expected to be completely gone in about 100 million years.

What are Saturn’s rings made of?

The rings are not solid. They are made of billions of individual particles of ice and rock. The main, bright rings are over 99% pure water ice. These particles range in size from microscopic dust grains to boulders as large as a house.

How old are Saturn’s rings?

The rings are surprisingly young, not old like the planet. Based on their “clean” icy composition and their low mass, scientists believe the rings are only between 10 million and 100 million years old. This means they likely formed while dinosaurs were still on Earth.

How did Saturn get its rings?

The leading theory is that the rings are the debris from a large, icy moon that got too close to Saturn and was torn apart by the planet’s gravity. This moon, nicknamed “Chrysalis,” would have been shredded when it crossed the “Roche limit,” with its icy fragments spreading out to form the rings we see today.

Do other planets have rings like Saturn?

Yes, but they are not as impressive. Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune all have ring systems. However, their rings are very faint, dark, and thin, and are made of dusty, rocky material instead of bright ice, which is why they are not as famous as Saturn’s.

When is the next time Saturn’s rings will “disappear” from view?

The next ring plane crossing, when the rings will appear to vanish, will happen on March 23, 2025. After that, the next time this illusion will occur is in the year 2038. Our view of the rings will be at its widest and most open in 2032.

What is the Roche limit?

The Roche limit is an invisible boundary around a planet or other large body. Inside this limit, the tidal force, or gravitational pull, of the planet is so strong that it will tear apart any smaller body (like a moon or comet) that is held together only by its own gravity. This is how scientists believe Saturn’s rings were formed.