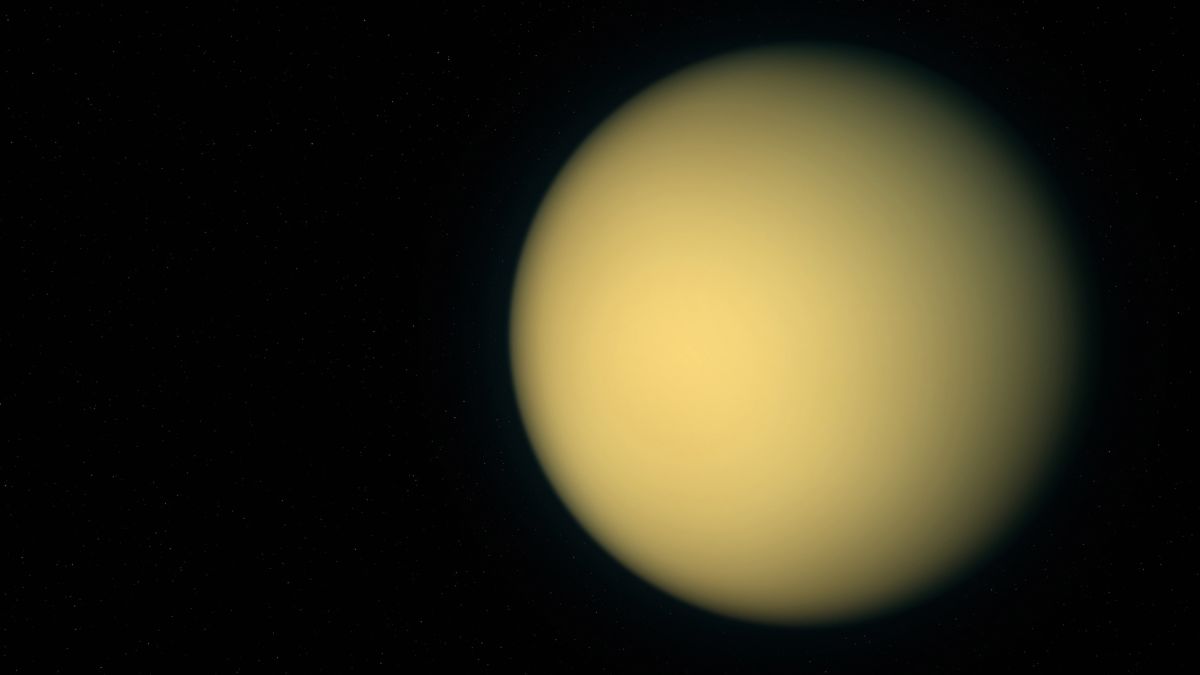

Our solar system is filled with amazing and mysterious places. We have giant gas planets, rocky worlds, and icy moons. But one moon stands out as truly special: Titan. Titan is the largest moon of Saturn, and it is one of the most Earth-like places we have ever found. It has a thick atmosphere, clouds, rain, rivers, lakes, and seas. This sounds familiar, but there is a major difference. On Titan, all this weather is made of liquid methane and ethane, not water.

NASA is preparing one of its most exciting missions ever to visit this strange world. It is called Dragonfly. This mission is not sending a rover that crawls on the ground, like the ones on Mars. Instead, NASA is sending a car-sized, nuclear-powered drone. This flying robot, officially called a rotorcraft, will be able to fly through Titan’s hazy orange skies. It will leapfrog across the surface, landing in different spots to study the ground.

This is a very new and bold way to explore another world. It has never been done before, except for the small helicopter that hitched a ride with the Mars Perseverance rover. The Dragonfly mission is a massive project, and it makes us ask a big question: Out of all the places in the solar system, why is NASA putting so much effort into sending a flying drone to Titan?

What Makes Titan So Special in Our Solar System?

Titan is special for many reasons. First, it is the only moon in our entire solar system that has a thick, dense atmosphere. Most moons, including our own, have no air at all. Titan’s atmosphere is actually four times denser, or thicker, than Earth’s. If you were standing on the surface, the air pressure would feel a little like being at the bottom of a swimming pool. This atmosphere is mostly nitrogen, just like Earth’s. This makes Titan very different from any other world we know.

Because of this thick atmosphere, Titan also has weather. But it is a very alien kind of weather. The moon is extremely cold, with an average surface temperature of around minus 179 degrees Celsius (minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit). At this temperature, water is frozen as hard as rock. In fact, the “bedrock” and mountains on Titan are made of this super hard water ice. But on Titan, other chemicals that are gases on Earth, like methane, can exist as liquids. This leads to a “methane cycle” that is just like Earth’s water cycle.

Sunlight in Titan’s upper atmosphere breaks down methane gas. This process creates a thick, orange smog or haze that hides the surface from view. This smog is made of complex organic molecules. These molecules are chemicals that contain carbon, a key ingredient for life. Scientists call this smog “tholins.” These tholins slowly rain down from the sky, coating the entire moon in a layer of dark, organic “gunk.” This smog also helps create methane clouds, which eventually lead to rain. This rain is not water, but liquid methane. This methane rain forms rivers that carve channels into the icy ground. These rivers flow into vast lakes and seas, some of which are larger than Earth’s Great Lakes.

Why Is Titan a Clue to the Origins of Life?

The main reason NASA is so interested in Titan is because of all those organic “tholin” molecules. Titan is like a giant laboratory for studying “prebiotic chemistry.” This sounds complicated, but it just means the chemical steps that happen before life begins. It is the study of how simple, non-living chemicals (like methane and nitrogen) can combine to form the complex molecules needed to build life. These complex molecules include things like amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins.

Scientists believe that billions of years ago, the very young Earth might have had a similar atmosphere. Before life appeared on our planet, Earth’s air was also filled with nitrogen and methane, and it lacked the oxygen we breathe today. The same kind of chemical reactions that are happening on Titan right now may have also happened on early Earth. On Earth, this process eventually led to the first living cells. On Titan, the process is happening in a deep freeze.

By going to Titan, we can study this process as it is happening. It is like having a “frozen record” of what Earth was like before life began. Dragonfly’s job is to land on the surface, scoop up this organic material, and see just how complex it has become. It will be looking for the specific building blocks that are essential for life as we know it. Did Titan’s chemistry create amino acids? Did it create other molecules that life uses? Answering these questions on Titan could help us finally understand the mystery of how life started here on Earth.

What Did We Learn from the Cassini-Huygens Mission?

We actually have landed on Titan before, but it was a very different kind of mission. In 2005, the Cassini-Huygens mission, a joint project between NASA and the European Space Agency, arrived at Saturn. The main Cassini spacecraft stayed in orbit, studying Saturn and its moons for over 13 years. But it also carried a small lander called Huygens. The Huygens probe was designed to do one thing: drop through Titan’s atmosphere and land on the surface.

This was a huge success. The Huygens probe became the first and only spacecraft to ever land on a world in the outer solar system. As it parachuted down for two and a half hours, it took amazing pictures. It showed us a landscape that looked strangely familiar. We saw deep river channels and what looked like a coastline. When it landed, it hit the ground with a “thud” in a damp, sandy area. The “sand” was likely made of organic tholins, and the “dampness” was from liquid methane. The pictures from the surface showed rounded “rocks” scattered around the landing site, which were almost certainly chunks of water ice, rounded and smoothed by flowing liquid.

While Huygens only survived for a few hours on the surface, the Cassini orbiter flew past Titan over 100 times. Using powerful radar that could see through the thick orange haze, Cassini mapped the moon’s surface. It is how we discovered the giant seas, like Kraken Mare, and the vast fields of dark sand dunes that circle Titan’s equator. Cassini also gave us the strongest evidence that Titan is hiding another secret: a huge ocean of liquid water and ammonia, buried deep beneath its icy crust. The Huygens probe gave us our first taste, and Cassini showed us the map. But they were limited. Huygens could not move, and Cassini could not touch the ground. They showed us why we had to go back with a more capable explorer.

Why Send a Flying Drone Instead of a Rover?

When we explore Mars, we use rovers like Curiosity and Perseverance. These rovers are fantastic, but they are very slow. A rover might only drive a few miles in an entire year. On Titan, the most interesting scientific locations are very far apart. There are the organic sand dunes, the floors of impact craters, and the icy plains. A rover would never be able to visit all these different places in one mission. The distances are just too great.

This is where Titan’s unique environment provides a perfect solution. Two things make Titan the best place in the solar system for a flying machine. The first is its thick, dense atmosphere. Because the air is four times thicker than Earth’s, it provides much more “lift” for wings or rotors. It is much easier to “grip” the air. The second reason is Titan’s low gravity. Because Titan is smaller than Earth, its gravity is much weaker, only about 14% of what we feel. This means the Dragonfly drone will be much lighter.

When you combine a thick atmosphere with low gravity, flying becomes incredibly easy. It takes very little energy to get off the ground and stay in the air. This makes a rotorcraft the ideal way to explore. Dragonfly will be able to do something no rover can: it will “leapfrog” across the landscape. It will fly for maybe 30 minutes, covering several miles, and then land in a completely new and interesting spot. It will stay there for one full Titan day (which is 16 Earth days), running its science experiments and recharging its batteries. Then, it will take off again and fly to another spot. Over its mission, NASA expects Dragonfly to fly over 175 kilometers (more than 100 miles). This is more than double the total distance driven by all the Mars rovers combined over several decades. This incredible mobility will allow Dragonfly to explore dozens of different locations.

How Will Dragonfly Stay Powered So Far from the Sun?

One of the biggest challenges for any mission in the outer solar system is power. Titan is almost ten times farther from the Sun than Earth is. The sunlight that reaches Titan is about 100 times weaker than the sunlight we get. This weak light is then blocked even more by Titan’s thick, hazy atmosphere. Because of this, solar panels are completely useless. The mission needs a power source that can work in the dark and the extreme cold for many years.

The solution is a “nuclear battery.” This is officially called a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, or MMRTG. This is not a nuclear reactor that splits atoms. Instead, it is a much simpler and safer device. It contains a few kilograms of plutonium-238, a special material that naturally gets very hot as it radioactively decays. This steady, reliable heat is captured by special materials called thermocouples. These thermocouples turn the heat directly into electricity. There are no moving parts, so it is extremely reliable.

This is a proven technology. The Mars Curiosity and Perseverance rovers both use an MMRTG to power them. The famous Voyager 1 and 2 probes, which were launched in 1977 and are now in interstellar space, are still working thanks to a similar nuclear power source. Dragonfly’s MMRTG will provide a constant, low-level supply of electricity, about 100 watts. This power will be used to keep the drone’s computers and instruments warm in the freezing cold. It will also be used to slowly charge a large lithium-ion battery, similar to a battery in an electric car. When it is time to fly, the drone will draw a huge burst of power from the battery to spin its eight rotors. After it lands, the MMRTG will spend the next 16 Earth days slowly recharging the battery for the next flight.

What Science Tools Will Dragonfly Use to Study Titan?

Dragonfly is not just a drone; it is a complete, mobile chemistry lab. To understand Titan’s prebiotic chemistry, it carries a set of powerful instruments. The most important one is called DraMS, which stands for the Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer. A mass spectrometer is basically a “chemical nose.” It is an instrument that can identify different molecules by “weighing” them. It is the key tool for finding the building blocks of life.

To get a sample into DraMS, Dragonfly uses a drill system called DrACO (Drill for Acquisition of Complex Organics). Dragonfly has two of these drills, one on each of its landing skids. When it lands in a new spot, it will lower a drill and bore into the surface material, whether it is hard water ice or soft organic sand. The drill will collect a tiny sample, less than a gram, and feed it into a tube. This sample is then “sucked” up into the main body of the lander using a puff of gas.

Once inside, the sample is dropped into a tiny oven and “baked” at a high temperature. This turns the solid sample into a gas. This gas is then fed into the DraMS instrument. DraMS separates all the different molecules in the gas and identifies them one by one. This is how scientists will find out if amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, or other important organic molecules are present on Titan’s surface. In addition to this main instrument, Dragonfly also carries a “weather station” called DraGMet. This tool will measure the temperature, pressure, wind speed, and humidity (methane humidity) on Titan. It also has a seismometer to listen for “titanquakes.” These tiny quakes can help scientists learn about the thickness of Titan’s ice crust and get more details about the liquid water ocean hidden deep below.

Where Will Dragonfly Land and What Will It Do?

The Dragonfly mission has a very clear and exciting exploration plan. The launch is planned for July 2028, but because Titan is so far away, the journey will take a long time. Dragonfly is scheduled to arrive at Titan and land in the year 2034. The chosen landing area is called the “Shangri-La” dune fields. This is a large, flat region near Titan’s equator that is covered in the dark, organic sand dunes that Cassini spotted. This is a perfect first stop because these dunes are made of the “tholin” gunk that has been raining down from the atmosphere for millions of years. It is a huge, accessible pile of the exact chemical ingredients that Dragonfly wants to study.

Dragonfly will spend the first part of its mission exploring these dunes. It will take several “leaps,” flying from one dune to another, drilling samples, and analyzing the material to see what it is made of. This will give scientists a baseline understanding of the organic chemistry on Titan’s surface. After it finishes exploring the dunes, Dragonfly will begin a much longer journey. It will take a series of flights, covering many miles, as it travels toward its final and most important target: the Selk Crater.

Selk Crater is a 90-kilometer (50-mile) wide crater that was formed when a large asteroid or comet smashed into Titan long ago. This impact is what makes Selk Crater so exciting. Scientists believe the incredible energy and heat from this impact would have instantly melted the hard water-ice crust. This would have created a large, temporary “pool” of warm, liquid water at the bottom of the crater. This pool of liquid water would have mixed with all the rich, organic tholin material that was already on the surface. This creates the “recipe for life” all in one place: you have complex organic molecules, liquid water, and energy (heat). This “primordial soup” may have lasted for thousands of years before it froze again. This is the single best place on Titan to look for the most advanced signs of prebiotic chemistry. Dragonfly will fly to this crater, land inside it, and drill into the crater floor to find out just how far that chemistry went.

Conclusion

The Dragonfly mission is a bold leap in planetary exploration. It combines the mobility of a helicopter with the power of a sophisticated, nuclear-powered chemistry lab. It is being sent to Titan, one of the most fascinating and Earth-like worlds in our solar system, to answer one of the biggest questions we have: How does life begin? By studying the “frozen” chemistry of this alien moon, we hope to find the chemical pathways that led to life on our own planet.

This mission will show us a side of Titan we have only dreamed of. We will see high-definition pictures from the surface and fly over its mountains of ice and seas of methane. Dragonfly will fly through the air of another world to hunt for the building blocks of life in a place that is both alien and strangely familiar. If Dragonfly finds complex molecules like amino acids in the frozen soup of an impact crater on Titan, what might that tell us about the chances for life to get started on other worlds all across the universe?

FAQs – People Also Ask

When is the NASA Dragonfly mission going to launch?

The Dragonfly mission is currently scheduled to launch in July 2028. Because Titan is so far away, the spacecraft will take several years to travel through the solar system.

When will Dragonfly arrive at Titan?

Dragonfly is scheduled to arrive at Titan and land on its surface in the year 2034. The journey from Earth to Saturn’s system is long and complex.

How big is the Dragonfly drone?

Dragonfly is a large drone, often described as being about the size of a small car. It has eight rotors, arranged in four pairs, and is much larger and more complex than a hobby drone.

What is prebiotic chemistry?

Prebiotic chemistry is the study of the chemical reactions that can create the complex building blocks of life (like amino acids) from simple, non-living molecules. It is the chemistry that happens before life itself begins.

Why is Titan’s atmosphere orange?

Titan’s atmosphere is a hazy orange color because of chemicals called “tholins.” Sunlight and radiation from Saturn break down methane gas in the upper atmosphere, and these simple molecules recombine to form complex, smog-like organic particles that fill the air and give it an orange tint.

Are there rivers and lakes on Titan?

Yes, Titan is the only other place in the solar system known to have liquid on its surface in the form of rivers, lakes, and seas. However, these are not made of water; they are filled with liquid methane and ethane.

Why can a drone fly so easily on Titan?

Flying is much easier on Titan than on Earth for two reasons. First, Titan’s atmosphere is four times thicker (denser) than Earth’s, which gives the rotors more “air” to push against for lift. Second, Titan’s gravity is much weaker (only 14% of Earth’s), making the drone much lighter.

How cold is it on Titan?

Titan is extremely cold. The average surface temperature is about minus 179 degrees Celsius (minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit). At this temperature, water is frozen as hard as rock.

Will Dragonfly look for aliens?

Dragonfly is not specifically looking for “aliens” or living microbes. Its main goal is to search for prebiotic chemistry, which means it is looking for the complex chemical ingredients and processes that could lead to life.

What is the Selk Crater?

Selk Crater is a 90-kilometer (50-mile) wide impact crater on Titan. It is Dragonfly’s main science target because scientists believe the impact melted the surface ice, creating a temporary pool of liquid water that mixed with Titan’s rich organic molecules, making it a perfect place to study the ingredients for life.