The James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, is the most powerful space observatory ever built. It has been scanning the skies and has found something amazing that is making scientists rethink everything. It has spotted the oldest, most distant supermassive black hole we have ever seen. This object is not just a little old; it comes from the “cosmic dawn,” the time when the very first stars and galaxies were lighting up the universe. We are seeing it as it was over 13 billion years ago.

Finding a black hole from this early time is a huge deal. But what really shocked scientists is its size. This black hole is gigantic, weighing in at millions of times the mass of our own Sun. According to all our previous theories, it should not exist. It is far too big, far too early. It is like finding a fully grown adult in a nursery of newborns. This discovery breaks our understanding of how these cosmic giants are supposed to grow. How can something so massive form so quickly after the universe itself began?

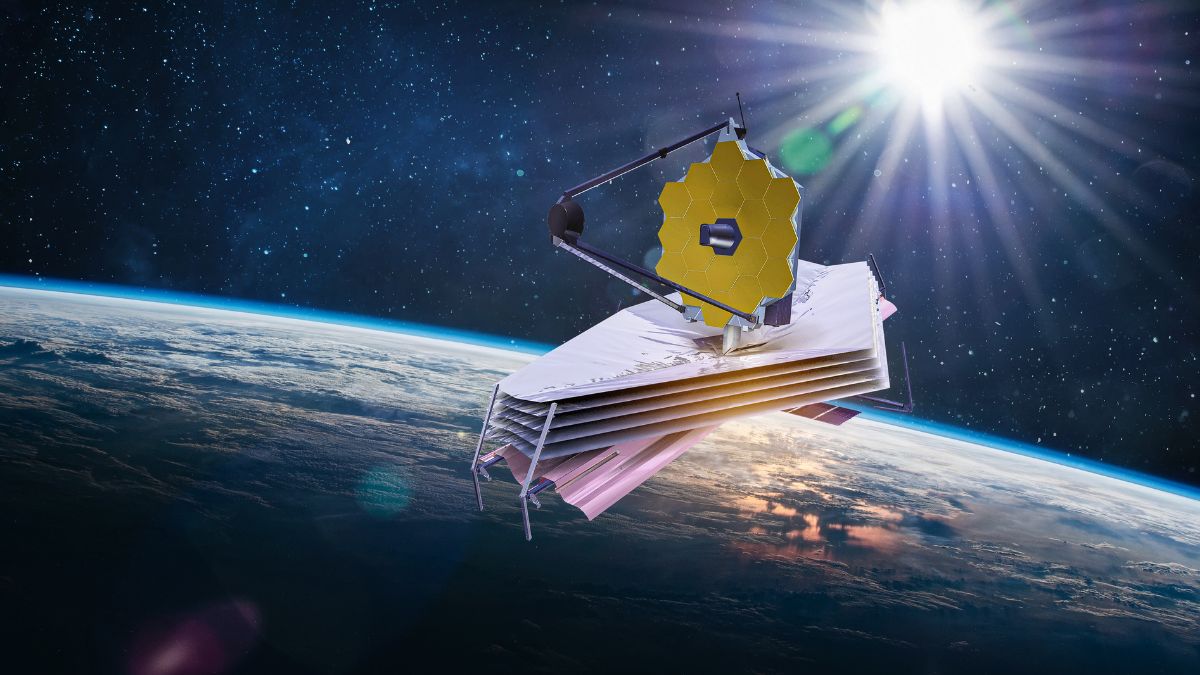

What Is the James Webb Space Telescope?

The James Webb Space Telescope is a special kind of observatory. Many people call it the successor to the famous Hubble Space Telescope, but it is very different. While Hubble sees the universe mostly in the same kind of light our eyes see (visible light), Webb is designed to see in infrared light. This is the key to its power. Infrared light is a type of light we feel as heat, and it is invisible to our eyes. This special vision allows Webb to do two incredible things. First, it can peer through the thick clouds of cosmic dust that block Hubble’s view, letting us see stars being born inside.

Second, and most importantly, it allows Webb to be a time machine. The universe has been expanding ever since it began with the Big Bang. As the universe expands, the light from the most distant galaxies gets stretched out during its long journey to us. This stretching process, called “redshift,” changes light from visible light into infrared light. The farther away an object is, the more its light is redshifted. Webb, with its huge, gold-coated mirror, is built specifically to catch this faint, stretched light. By capturing light that has traveled for over 13.4 billion years, Webb is not seeing the universe as it is today. It is seeing the universe as it was just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, giving us baby pictures of the very first galaxies.

What Exactly Is a Black Hole?

Before we can understand why this discovery is so shocking, we need to know what a black hole is. A black hole is an object in space where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape its pull. Not a planet, not a star, and not even light, the fastest thing in the universe. This is why they are called “black.” Because no light can escape, we cannot see them directly. The edge of a black hole is called the “event horizon.” If you cross this boundary, you can never get back out. It is the ultimate point of no return.

Scientists believe there are two main types of black holes. The first kind is called a stellar-mass black hole. These are the “common” ones. They form when a single, very massive star (much bigger than our Sun) runs out of fuel and dies. The star’s core collapses under its own immense gravity, crushing itself down into an incredibly tiny point. These black holes are typically 5 to 20 times the mass of our Sun. The second kind is the one we are interested in: the supermassive black hole. These are the true monsters of the cosmos. They are not 20 times the mass of our Sun; they are millions or even billions of times more massive. Scientists believe that one of these giants sits at the center of almost every large galaxy, including our own Milky Way.

How Do Scientists Find Black Holes If They Are Invisible?

This is an excellent question. If black holes are invisible, how did Webb find one? It is true that we cannot see the black hole itself, but we can see the chaos it creates around it. Scientists use a few clever indirect methods to find them. One way is to watch the stars and gas nearby. At the center of our own Milky Way, astronomers watched for decades as stars whipped around a single, invisible point at incredibly high speeds. The only thing with enough gravity to make stars move that fast was a supermassive black hole, which we now call Sagittarius A*.

The second, and more common, way to find them is to look for them while they are eating. The black hole Webb found is not sleeping; it is an “active” black hole. As gas, dust, and stars get too close, the black hole’s gravity pulls them in. This material does not fall straight in. Instead, it forms a massive, swirling pancake of superheated gas called an “accretion disk.” The material in this disk spins around the black hole at nearly the speed of light. The friction in this disk heats the gas to millions of degrees, causing it to glow brighter than all the stars in its galaxy combined. This incredibly bright, energetic lighthouse, powered by a feeding black hole, is called a quasar. This is what Webb saw. It did not see the black hole, but it saw the unmistakable, brilliant light of the superheated gas being eaten by one.

What Did the Webb Telescope Actually Discover?

The Webb telescope was pointing at one of the most distant galaxies ever found, a galaxy named GN-z11. What makes GN-z11 so special is when we are seeing it. The light from this galaxy has traveled for so long that we are seeing it as it was just 400 to 440 million years after the Big Bang. To put that in perspective, the universe is about 13.8 billion years old. We are seeing this galaxy when the entire universe was only 3% of its current age. It is from the very first generation of galaxies.

Inside this tiny, infant galaxy, Webb’s sensitive instruments detected the tell-tale signs of a quasar. It found gas moving at extreme speeds and glowing with a brightness that could not be explained by stars alone. This was the smoking gun for an active supermassive black hole. But here is the shocking part: When scientists calculated its size, they found it was already about 1.6 million times the mass of our Sun. This is a fully-formed supermassive black hole in a galaxy that is just getting started. To make matters even stranger, this black hole is surprisingly large compared to its galaxy. In our Milky Way, our central black hole is only 0.1% of the galaxy’s total mass. In GN-z11, the black hole is a few percent of its galaxy’s mass. It is a giant monster in a tiny house.

Why Is Finding This Black Hole Such a Big Problem?

This discovery creates a massive problem for our theories. For decades, we had a standard story for how supermassive black holes grow. We called it the “bottom-up” model. This theory said that black holes start small. A giant star would die, creating a “seed” black hole of maybe 10 to 100 times the sun’s mass. Then, this seed would slowly grow over billions of years. It would grow by pulling in nearby gas and dust, and by merging with other small black holes when galaxies collided. It is a slow, steady process, like filling a swimming pool with a dripping faucet.

This process has a “speed limit.” There is a physical rule called the “Eddington limit.” This rule says a black hole can only eat so fast. If it tries to eat too much gas too quickly, the radiation and heat blasting from its accretion disk become so intense that they physically push away any more gas from falling in. The black hole essentially chokes itself on its own meal. The problem with the black hole in GN-z11 is that it is far too big, far too early. Even if a seed black hole formed right after the Big Bang and started eating as fast as physically possible—at the Eddington limit 100% of the time—it could not reach 1.6 million solar masses in just 400 million years. There simply was not enough time. The math does not work.

How Could This Black Hole Have Formed So Quickly?

The existence of this “impossible” black hole means our old story must be wrong, or at least incomplete. Scientists are now racing to come up with new theories, and a new leading idea has emerged. It is called the “direct collapse” model, and it suggests black holes did not all start small. This theory says that in the very early universe, conditions were completely different. The first stars had not yet cooked up heavy elements like iron and carbon. The universe was almost entirely pure hydrogen and helium gas.

Under these pristine conditions, a truly gigantic cloud of this original gas—perhaps millions of times the mass of the Sun—could have collapsed all at once under its own gravity. Because this gas did not have the heavy elements to help it cool down and break into smaller clumps, it did not form thousands of normal stars. Instead, the entire cloud collapsed directly into a single, massive object: a “heavy seed” black hole. This seed would not be 10 times the mass of the Sun; it would be born at 10,000 or even 100,000 times the mass of the Sun. If you start with a seed this massive, it is possible for it to grow to 1.6 million solar masses in 400 million years. It is like filling the swimming pool by starting with a giant water truck instead of a dripping faucet.

What Does This Discovery Tell Us About the First Galaxies?

This discovery is rewriting the first chapter of the universe’s history. We used to have a chicken-and-egg question: Which came first, the galaxy or its supermassive black hole? The old theory said the galaxy came first. A galaxy would form, stars would live and die, and a black hole would slowly grow in the center over time. This new discovery from Webb suggests the opposite may be true. It is possible that these “direct collapse” black holes formed first, or at the same time as the galaxy.

These giant black holes may have acted as the “seeds” or “anchors” for the first galaxies. Instead of a black hole growing inside a galaxy, the first galaxies may have formed around these pre-existing giant black holes. The immense gravity of these heavy seeds would have pulled in gas and dark matter, creating the cosmic scaffolding for the first stars to form. Furthermore, the intense energy (the quasar) blasting from these eating black holes would have had a huge impact on their small host galaxies. This energy could have blown gas out of the galaxy, stopping new stars from forming, or it could have compressed gas, triggering new bursts of star birth. It shows that from the very beginning, black holes were not just quiet objects; they were active engines shaping the universe we see today.

Conclusion

The James Webb Space Telescope is doing exactly what it was built to do: find the unexpected and challenge our deepest ideas about the cosmos. By finding this “impossibly” large black hole in the galaxy GN-z11, it has shown us that the universe was building monsters just 400 million years after the Big Bang. This single discovery has shaken our understanding of how the first supermassive black holes were born, forcing us to abandon old, slow-growth models.

The new, exciting idea of “direct collapse” black holes—where giant clouds of pristine gas collapsed into massive seeds—is now the best explanation we have. This suggests that the relationship between galaxies and their central black holes is far more ancient and deeply connected than we ever knew. Webb has opened a new window into the cosmic dawn, and it is showing us that it was a far more dramatic and busy place than we ever imagined. If the first 400 million years were this full of surprises, what else is hiding in the darkness, waiting to be found?

FAQs – People Also Ask

What is the name of the oldest black hole found?

The oldest supermassive black hole found so far is located in a galaxy called GN-z11. The James Webb Space Telescope detected its bright quasar, the light from its accretion disk, as it was 13.4 billion years ago.

How old is the oldest black hole?

We are seeing this black hole as it existed only about 400 million years after the Big Bang. Since the universe is 13.8 billion years old, this means we are looking at an object from when the universe was in its earliest infancy, at only 3% of its current age.

How does the James Webb telescope see back in time?

The telescope sees back in time by looking at objects that are extremely far away. Light, the fastest thing in the universe, still takes time to travel. The light from galaxy GN-z11, for example, took over 13.4 billion years to reach us. So, we are seeing the galaxy as it was 13.4 billion years ago.

What is a supermassive black hole?

A supermassive black hole is the largest type of black hole. While normal black holes might be 10 times the mass of our Sun, supermassive ones are millions or even billions of times the mass of our Sun. Scientists believe one is at the center of nearly every large galaxy.

What is the difference between Webb and Hubble?

The main difference is the type of light they see. The Hubble telescope sees mostly visible and ultraviolet light, like our eyes. The James Webb telescope is much larger and is designed to see infrared light, which we feel as heat. This infrared vision allows Webb to see through dust and, more importantly, see the “redshifted” light from the most distant objects in the universe.

What is a quasar?

A quasar is not the black hole itself, but the extremely bright light that comes from a black hole while it is eating. As gas and dust fall into a supermassive black hole, they form a spinning disk that heats up to millions of degrees, shining brighter than an entire galaxy. This is the “active” phase of a black hole.

Why can’t black holes grow infinitely fast?

Black holes have a “speed limit” for eating called the Eddington limit. If a black hole pulls in gas too quickly, the gas gets so hot that it shines with incredible power. This light itself creates a pressure (radiation pressure) that physically pushes away any more gas from falling in, temporarily choking the black hole.

What is a “direct collapse” black hole?

This is a new theory to explain how black holes like the one in GN-z11 got so big, so fast. Instead of forming from a single star, this theory suggests that a gigantic cloud of pure, early-universe gas (millions of times the Sun’s mass) collapsed all at once, directly into a “heavy seed” black hole of 10,000 to 100,000 solar masses.

Is there a black hole in our galaxy?

Yes, there is a supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy. It is called Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”). It is about 4 million times the mass of our Sun and is currently in a quiet, “sleeping” phase, meaning it is not actively eating like a bright quasar.

Will the James Webb telescope find even older black holes?

It is very likely. This is one of the telescope’s primary missions. Astronomers are now actively using Webb to scan other distant galaxies from the cosmic dawn. The discovery in GN-z11 may be just the first of many “impossible” objects that will help us rewrite the story of the early universe.