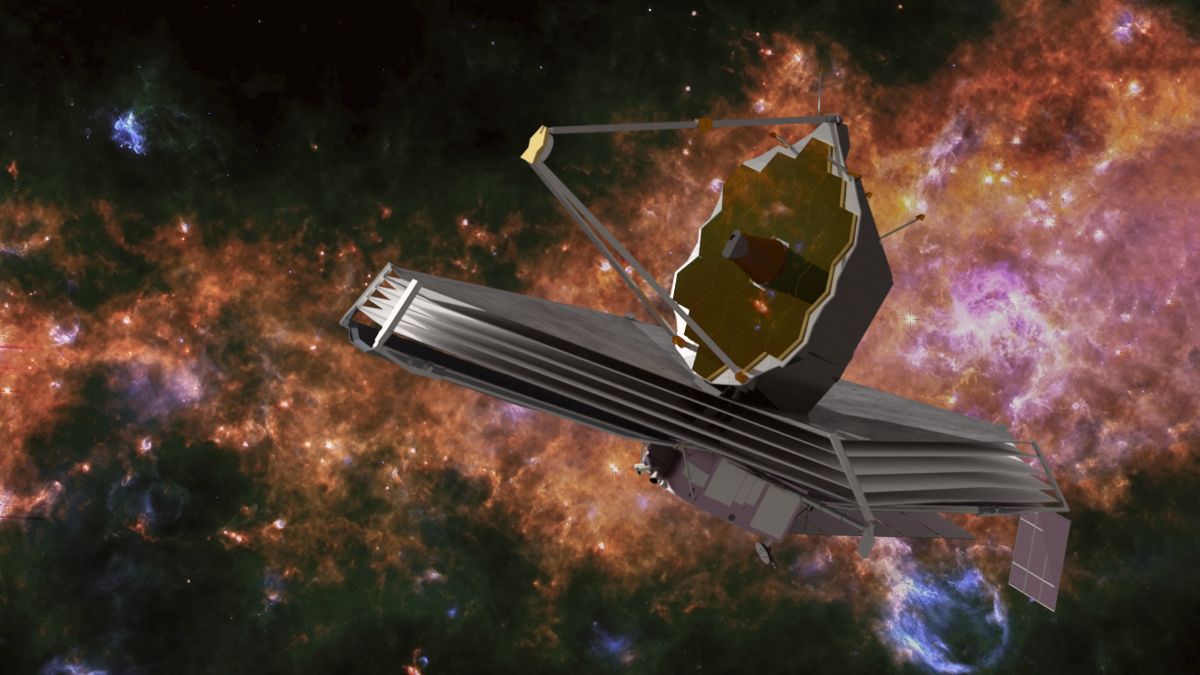

The James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, is one of the most powerful scientific instruments ever built. We often hear it called a “time machine” that can look back to the very beginning of the universe. It sends us amazing pictures of distant, glittering galaxies and colorful nebulas, showing us parts of space we have never seen before. Because it is so powerful, many people wonder if this telescope can finally show us the Big Bang itself—the very moment our universe began.

The simple answer to this question is no, the Webb telescope cannot see the Big Bang. This is not because the telescope is not strong enough or because scientists are not pointing it in the right direction. The reason is more interesting than that. It is because of what the universe was like in its earliest moments. For hundreds of thousands of years after it began, the universe was completely dark and filled with a thick, hot “fog” that no telescope, not even Webb, can see through.

This might sound disappointing, but the true story of what Webb can see is just as exciting. It is built to look at the first things that formed after this dark fog cleared. It is hunting for the very first stars and the first galaxies that ever lit up the cosmos. So, if Webb cannot see the “bang” itself, what is the oldest thing in the universe that we can see?

What Is the Big Bang (and Why Can’t We ‘See’ It)?

When we hear the phrase “Big Bang,” we often picture a giant explosion, like a bomb going off in the middle of empty space. But that is not quite right. The Big Bang was not an explosion in space; it was the beginning of space itself, along with time and all the matter and energy in the universe. Everything we know started from a single point that was incredibly hot and incredibly dense. This point did not appear in a dark, empty room; the “room” itself, all of space, began with it and has been expanding ever since.

This is the first reason we cannot “see” it. There is no single spot in the sky to point a telescope and say, “That is where the Big Bang happened.” The Big Bang happened everywhere, at every point in space, all at once. But there is an even more important reason. For the first 380,000 years of its life, the universe was not transparent. It was completely opaque. It was filled with a “soup” of particles—protons, neutrons, and electrons—that were zipping around in a plasma that was hotter than the surface of the Sun.

In this hot, dense fog, light particles, called photons, could not travel freely. As soon as a photon tried to move, it would crash into a free-floating electron and be scattered in a different direction. It was like being in the thickest, densest fog you can imagine. You cannot see a light bulb that is only a few feet away because the light is scattered by the water droplets. In the early universe, this “fog” of particles blocked all light from traveling. No light from this time can reach us today, which means no telescope can ever see into it. This entire period is known as the “cosmic dark ages.”

What Is the Oldest Light in the Universe?

If we cannot see the first 380,000 years, what happens right after that? This is where the story gets really interesting. As the universe continued to expand, it also cooled down. After about 380,000 years, it cooled enough for the electrons to slow down and “recombine” with the protons and neutrons, forming the first stable atoms, mostly hydrogen and helium. When this happened, the “fog” suddenly cleared. The photons that were trapped in the plasma were finally set free and could travel in straight lines across the universe for the first time.

This first, ancient light that was set free is still traveling through space today, and it is the oldest light we can possibly detect. It is called the Cosmic Microwave Background, or CMB. This light is essentially the “afterglow” of the Big Bang. It is a faint, leftover heat from that first fiery moment, and it fills the entire sky. It is not something the Webb telescope was built to see. The CMB is not visible or infrared light; because the universe has expanded so much, this light has been stretched into microwaves.

We have built other, very special telescopes (like the Planck satellite and the WMAP probe) that are designed to map this microwave light. When they take a “picture” of the CMB, it looks like a faint, blotchy pattern of tiny temperature differences. This “baby picture” of the universe is incredibly important. It shows us what the universe looked like when it was just 380,000 years old, and those tiny blotches were the “seeds” that would later grow into the giant galaxies and clusters of galaxies that we see today. So, the CMB is the oldest light we can see, but Webb is looking for the first things that formed after this light was released.

How Does the Webb Telescope Work Like a Time Machine?

To understand what Webb does, we first need to understand how looking far away is the same as looking back in time. This is all because of the speed of light. Light travels very fast, but it does not travel instantly. When you turn on a lamp in your room, the light seems to fill the room immediately, but it is actually taking a tiny fraction of a second to travel from the bulb to your eyes. For things here on Earth, this delay does not matter. But in space, the distances are huge.

The Sun, for example, is about 93 million miles away. It takes light about 8 minutes and 20 seconds to travel from the Sun to Earth. This means when you look at the Sun (which you should never do directly!), you are not seeing it as it is right now. You are seeing it as it was over 8 minutes ago. If the Sun were to suddenly disappear, we would not know about it for more than 8 minutes.

This same idea applies to everything in space. The next nearest star to us, Proxima Centauri, is over 4 light-years away. The light we see from it tonight left that star more than 4 years ago. The Andromeda Galaxy, our closest large galactic neighbor, is 2.5 million light-years away. The light Webb sees from Andromeda is 2.5 million years old. The telescope is, quite literally, looking at a 2.5-million-year-old version of that galaxy.

Webb was built to take this to the extreme. It is designed to find galaxies that are 13 billion light-years away, or even more. Since the universe itself is about 13.8 billion years old, Webb is seeing light that has been traveling for almost the entire age of the universe. It is seeing these galaxies as they were when they were just “babies,” only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. This is why it is called a time machine. It is not science fiction; it is just using the fixed speed of light to our advantage.

Why Does Webb Use Infrared Light to See the Past?

So, if Webb is looking for the first stars, why is it an infrared telescope? We know that stars, especially hot, young ones, shine brightly in visible light and even ultraviolet (UV) light. Our own eyes see visible light, which is the rainbow of colors from violet to red. Infrared is a type of light with a longer wavelength than red light. We cannot see it, but we can feel it as heat. Your TV remote control also uses infrared light to send signals. It seems strange to build a “star-seeing” telescope that cannot see the light that stars seem to make.

The reason for this is one of the most important concepts in astronomy: redshift. We know the universe is expanding. All the galaxies are moving away from each other. A good way to think about this is to imagine baking raisin bread. As the dough (space) rises and expands, it carries all the raisins (galaxies) along with it, moving them farther apart from each other. As light travels through this expanding space for billions of years, the light waves themselves get stretched.

Imagine a light wave that starts from a very distant, very first star. It might start as blue or ultraviolet light, which has a short, scrunched-up wavelength. But as it travels through expanding space for 13 billion years, that wave gets stretched out. A short, blue wave gets stretched into a longer, red wave. If it travels for even longer, it gets stretched past red light altogether, becoming infrared light. This stretching effect is called “redshift” because the light is shifted toward the red (and infrared) end of the spectrum.

The light from the very first galaxies is so old and has traveled so far that it is “extremely redshifted.” By the time that light finally reaches Webb’s mirror, it is no longer visible light. It is infrared light. This is why the Hubble Space Telescope could not see these first galaxies very well. Hubble is a master of visible and ultraviolet light, but it is mostly blind to the deep infrared. Webb is an infrared specialist. Its giant, gold-coated mirror is designed specifically to catch this ancient, stretched, “redshifted” light from the dawn of time.

What Is the Difference Between the Webb and Hubble Telescopes?

The James Webb Space Telescope is often called the “successor” to the Hubble Space Telescope, but it is more accurate to call it a partner. They are both amazing tools, but they were built to do very different jobs. The biggest difference, as we just saw, is the kind of light they see. Hubble is like our own eyes; it sees mostly visible light, the same “rainbow” that we do, along with some ultraviolet and a little bit of near-infrared. This makes it perfect for taking stunning, sharp pictures of “teenage” and “adult” galaxies that are closer to us.

Webb, on the other hand, is a dedicated infrared machine. It is designed to see the “baby” galaxies whose light has been redshifted all the way to infrared. This is why its mirror is coated in a thin layer of gold—gold is one of the best materials in the universe for reflecting infrared light. Another major difference is size. Webb’s primary mirror is over 21 feet (6.5 meters) across, which is almost three times wider than Hubble’s. A bigger mirror is like a bigger “light bucket.” It can collect more light, which allows Webb to see objects that are much fainter and much farther away than Hubble ever could.

Finally, their location is completely different. Hubble is in “low Earth orbit,” just a few hundred miles above the surface. We could even send astronauts in the Space Shuttle to repair it. But Webb is about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth, at a special, gravitationally stable point called L2. It was sent this far out for a very important reason. Because Webb sees infrared light (heat), it has to be kept incredibly cold. If it were near Earth, the heat from our planet and the Sun would blind its sensitive instruments. At L2, it can use a giant, five-layer sunshield (the size of a tennis court) to block all that heat, allowing the telescope to cool down to almost absolute zero. This extreme cold is essential for it to see the faint, infrared heat from the beginning of time.

What Are the First Galaxies Webb Has Found?

Before the Webb telescope was launched, scientists had theories about what the first galaxies would look like. They expected to find small, clumpy, and messy-looking “galaxy-starters” that were just beginning to pull themselves together. They thought the process of building a large, organized galaxy (like our own Milky Way) would take a very long time. What Webb found in its first year of operation, starting in 2022, was a complete surprise and has challenged many of our ideas about the early universe.

Webb immediately started finding galaxies that were incredibly distant. It found objects like JADES-GS-z13-0, which is currently one of the most distant and earliest galaxies ever confirmed. We are seeing this galaxy as it was just 320 million years after the Big Bang. This is an amazing record, but the type of galaxies it found was even more shocking. Webb found many early galaxies that were not small and clumpy at all. They were surprisingly large, bright, and already had well-formed structures, some even looking like small spiral or disk galaxies.

These discoveries have sent astronomers and physicists scrambling to update their models. How did these galaxies get so big, so fast? How did they form so many stars so quickly, when the universe was still so young? These are the new, exciting questions that Webb has created. It is like opening a history book about the earliest civilization and finding out they already had skyscrapers and superhighways. Webb is not just confirming old theories; it is actively rewriting the first chapter of cosmic history. It is showing us that the “cosmic dawn” was even more dramatic and busy than we ever imagined.

So, What Is the Cosmic Dawn and the Epoch of Reionization?

These two terms describe the time period that Webb was built to study. The “cosmic dark ages,” as we discussed, was the period after the CMB light was released (at 380,000 years) but before the first stars turned on. For millions of years, the universe was dark, transparent, and filled with a neutral gas of hydrogen and helium. Then, sometime around 100 to 200 million years after the Big Bang, something amazing happened: gravity had pulled enough of this gas together to ignite the very first stars. This moment is called the “Cosmic Dawn.” It is the first time the universe was filled with new light after the Big Bang’s afterglow faded.

These first stars were not like our Sun. Scientists believe they were giants, hundreds of times more massive, and lived very short, very violent lives. They burned incredibly hot, shining brightly in ultraviolet light. This powerful UV light then started to change the universe again. It began to zap the neutral hydrogen gas that filled all of space, stripping the electrons off the atoms. This process is called the “Epoch of Reionization.” These first stars and the first small galaxies that formed around them acted like beacons in the fog, clearing out the neutral gas and making the universe transparent in the way we know it today.

This entire process, from the first star turning on to the last bit of “fog” being cleared, may have taken a billion years. This is the great, unexplored chapter of our universe’s history that Webb is designed to read. It is trying to pinpoint exactly when the Cosmic Dawn happened. It is studying how the first galaxies took shape. And it is watching the process of reionization as it happened, helping us understand how the dark, gassy universe turned into the clear, star-filled cosmos we live in. Webb is the first and only tool we have that is powerful enough to see this critical transformation.

Conclusion

So, while the James Webb Space Telescope cannot see the Big Bang itself, its real job is arguably even more complex and revealing. It cannot look past the opaque “fog” of the universe’s first 380,000 years. And it was not designed to see the “first light” that was released when that fog cleared, which we call the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Instead, Webb’s mission is to see what happened next. It is a powerful infrared time machine, built to capture the ancient, “redshifted” light from the very first stars and galaxies that lit up the universe after the cosmic dark ages. It is already showing us that this “Cosmic Dawn” was more surprising than we ever thought, with galaxies growing bigger and faster than our theories predicted. Webb is not just looking at the past; it is helping us write the story of our own cosmic origins for the very first time.

By studying these first galaxies, we are learning how the universe transformed itself from a dark, simple soup of gas into the brilliant and complex place we see today. What new mystery about our cosmic history do you think Webb’s “time-traveling” eyes will uncover next?

FAQs – People Also Ask

Why can’t any telescope see the Big Bang?

The Big Bang was not an explosion in space but the start of space and time itself. More importantly, the universe was filled with a hot, opaque “fog” of particles for the first 380,000 years, making it impossible for any light from that time to travel to us today.

What is the oldest thing a telescope can see?

The oldest light any telescope can see is the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). This is the “afterglow” or leftover heat from the Big Bang, which was released when the universe’s “fog” cleared about 380,000 years after it began. Special microwave telescopes, not Webb, are built to see this.

How far back in time can the Webb telescope see?

The Webb telescope is designed to see light from over 13.5 billion years ago. This allows it to see the first stars and galaxies as they were when the universe was only a few hundred million years old, which is a period right after the “cosmic dark ages.”

Is the James Webb telescope better than Hubble?

They are not better or worse, just different. Hubble primarily sees visible light and is perfect for studying “teenage” and “adult” galaxies. Webb is larger and sees infrared light, which is necessary to study the “baby” galaxies from the very early universe whose light has been “redshifted.”

Why is the Webb telescope’s mirror coated in gold?

Gold is an almost perfect reflector of infrared light, which is the type of light Webb is built to detect. This thin gold coating makes its giant mirror extremely efficient at capturing the faint, stretched-out light from the most distant galaxies.

What is redshift and why is it important for Webb?

Redshift is the stretching of light waves as the universe expands. Light from the first stars and galaxies started as visible or ultraviolet light, but after traveling for 13+ billion years through expanding space, it has been stretched into infrared light. Webb is an infrared telescope specifically designed to catch this light.

Where is the James Webb Space Telescope located?

Webb is in a special orbit about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. This spot, called the second Lagrange point (L2), allows the telescope to stay very cold and use a giant sunshield to block heat from the Sun and Earth, which would otherwise blind its sensitive infrared instruments.

What has the Webb telescope discovered so far?

Webb has already found some of the most distant galaxies ever seen. Surprisingly, many of these early galaxies are much larger, brighter, and more structured than scientists had predicted, which is forcing them to rethink how quickly galaxies can form.

What are the ‘cosmic dark ages’?

This is the period in the universe’s history after the Cosmic Microwave Background was released (at 380,000 years) but before the very first stars formed (around 100-200 million years). During this time, the universe was transparent but dark, filled only with neutral hydrogen and helium gas.

Will the Webb telescope find alien life?

Webb’s main mission is to study the first galaxies, but it also has the ability to study planets orbiting other stars, called exoplanets. It can look at the atmospheres of these planets and search for “biosignatures,” such as water, methane, or carbon dioxide, which could be hints of life.