A black hole is one of the strangest and most powerful things in the entire universe. Scientists talk about them all the time, and we even have pictures of them. But this leads to a very big question. A black hole is “black” because its gravity is so strong that it traps everything, including all light. If no light can get out, it should be completely invisible. We cannot see it the same way we see a star or a planet. It does not shine, and it does not reflect light. It is a perfect patch of blackness in the blackness of space.

So, how do we study something we cannot see? It seems impossible, like trying to find a black cat in a dark room with your eyes closed. But scientists are very clever. They have found ways to “see” these invisible giants, not by looking at them, but by looking at how they affect everything around them. One of the most amazing ways we do this is by using the black hole’s own gravity as a giant magnifying glass. This special trick is called gravitational lensing. This article will explain exactly how we use gravity itself to find something that light cannot escape.

This whole idea might sound like science fiction, but it is a real tool that astronomers use every single day. We are going to break down how this works in very simple, easy steps. We will explore how a massive, invisible object can bend and warp the light from other stars and galaxies. We will also look at the other clues black holes leave behind, from the way they make nearby stars dance to the way they “eat” their meals. How do you take a picture of something that has no light?

What Is a Black Hole and Why Is It Invisible?

Before we can understand how to see a black hole, we need to know what it is. A black hole is not really a “hole” at all. It is not an empty space. Instead, it is a huge, huge amount of “stuff” (which scientists call “mass”) packed into an extremely tiny space. Think about our sun. It is giant and very heavy. Now, imagine crushing the entire sun down until it is smaller than a single city. The amount of stuff is the same, but the space it takes up is tiny. This would create a black hole.

Because all that stuff is squeezed so tightly, its force of gravity becomes incredibly strong. On Earth, gravity just holds you to the ground. But the gravity of a black hole is so powerful that it creates a special boundary around itself. This boundary is called the “event horizon.” You can think of the event horizon as the “point of no return.” If you get too close, you will be pulled in. It is like being in a boat near a giant waterfall. At first, you can row away. But there is a point where the water is moving so fast that no matter how hard you row, you cannot escape and will go over the edge. The event horizon is that edge for gravity.

The reason a black hole is “black” is because this point of no return applies to everything, even the fastest thing in the universe: light. A beam of light can travel very fast, but if it crosses the event horizon, it gets trapped. It cannot escape. It cannot bounce off the black hole and come back to our eyes. And the black hole does not make its own light, like a star does. Since no light can come from the black hole, it is perfectly, completely invisible. It is a “black hole” in the truest sense. This is the main problem for astronomers. They cannot just point a telescope and see one. They have to look for the clues it leaves behind.

What Is Gravitational Lensing?

The most important clue a black hole leaves is its gravity. This is where the idea of “gravitational lensing” comes in. The name sounds complicated, but the idea is simple, and it all comes from Albert Einstein. Over 100 years ago, Einstein came up with a new way to think about gravity. He said that gravity is not just a “pulling” force. Instead, he said that massive objects (like planets, stars, and black holes) actually bend or warp the “fabric” of space around them.

The easiest way to picture this is to think of space as a big, stretchy trampoline. If the trampoline is empty, it is flat. If you roll a marble across it, the marble will travel in a perfectly straight line. Now, place a heavy bowling ball in the middle of that trampoline. What happens? The bowling ball sinks down, creating a deep curve or “dip” in the fabric. This dip is a simple way to picture gravity. The heavier the object, the deeper the dip it creates.

Now, try to roll that same marble across the trampoline again. If the marble passes near the edge of the bowling ball’s dip, it will try to go straight, but the curve in the trampoline will force its path to bend. It will follow the curve. This is exactly what happens in space. A beam of light is like the marble. It always tries to travel in a straight line. But when a beam of light from a distant star travels past a massive object (like a black hole), it has to cross the “dip” in space that the object has made. The black hole’s gravity—its deep dip in spacetime—forces the path of the light to bend. This bending of light by gravity is what we call “gravitational lensing.” The black hole’s gravity acts just like a lens in a magnifying glass, which also bends light.

How Does Lensing Let Us ‘See’ the Invisible?

Now we can connect the two ideas. We have an invisible black hole, and we know that its massive gravity bends light. This is the key. We do not see the black hole (the “lens”), but we can see its effect on the light from things behind it. Imagine you are on Earth looking up at a distant, bright galaxy. Now, imagine that a black hole is floating in space, and it just happens to pass directly between you and that background galaxy. The black hole is completely invisible. You cannot see it. But the light from the background galaxy must travel past the black hole to reach your telescope.

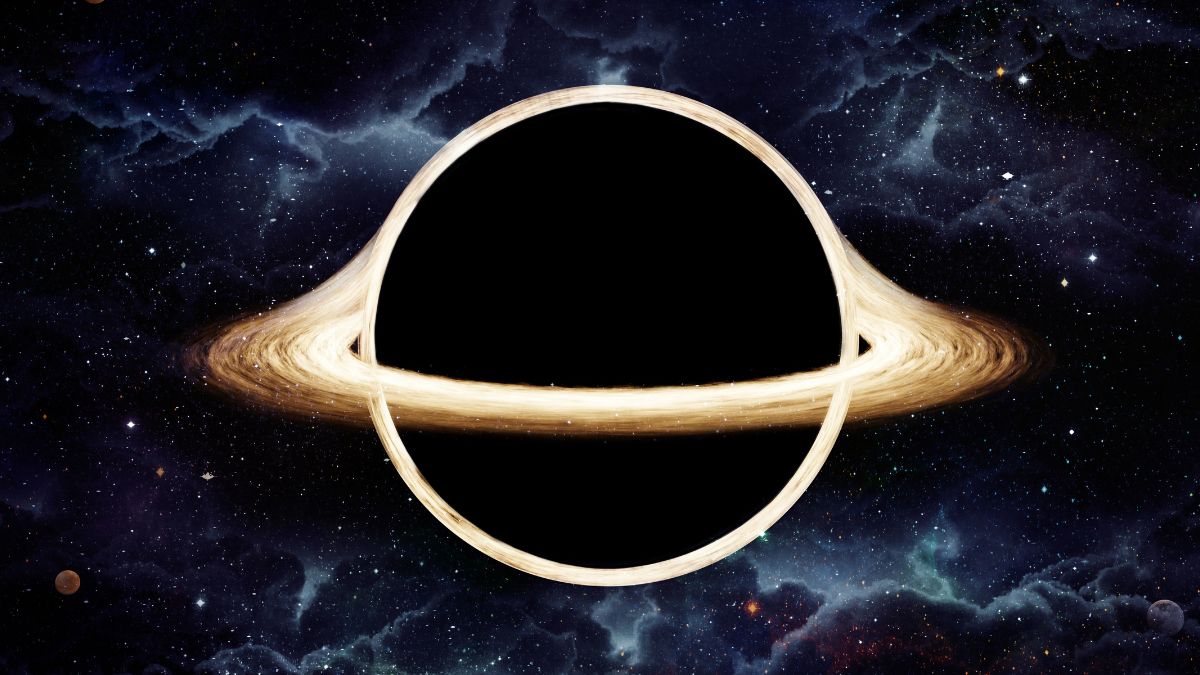

As that light passes the black hole, its powerful gravity (the deep “dip” in space) bends the light. It acts like a giant, cosmic magnifying glass. When the light finally reaches your telescope, it is no longer a simple dot. It has been warped, distorted, and magnified. What we see is a ghostly, weird shape. If the black hole, the galaxy, and Earth are lined up perfectly, the light from the background galaxy gets smeared into a beautiful, perfect circle of light. This is called an “Einstein Ring.” It looks like a glowing halo in space, with the invisible black hole hiding in the dark center.

If the alignment is not quite perfect, which is much more common, the light gets distorted in other ways. We might see the background galaxy stretched out into bright, glowing “arcs,” like bright bananas curving around a central empty spot. Or, the lens can be so strong that it splits the light into multiple images. We might look in the sky and see two, three, or even four pictures of the exact same galaxy! It looks like there are four galaxies, but it is really just one galaxy whose light has been split by the invisible black hole in front of it. When astronomers see these strange rings, arcs, or multiple images, it is a giant red flag. They know that something incredibly massive and invisible must be hiding in the middle, acting as the lens. We “see” the black hole by seeing the way it messes with the light from behind it.

Have We Ever Seen a Black Hole’s ‘Shadow’?

Yes, we have! You have probably seen the famous picture: a fuzzy, glowing orange donut. This was a huge breakthrough in 2019, and it is directly related to gravitational lensing. This picture was taken by a group called the Event Horizon Telescope, or EHT. The EHT is not just one telescope. It is a network of many powerful radio telescopes spread all across the in_the_world. They are in Hawaii, Chile, Spain, Arizona, and even the South Pole. By linking all these telescopes together with powerful computers, scientists created a “virtual” telescope as big as the entire planet Earth.

They needed a telescope this big to get a sharp enough picture to see something as “small” (in the sky) and as far away as a black hole’s event horizon. They pointed this giant Earth-sized telescope at a massive galaxy called M87, which is 55 million light-years away. At the center of M87 is a supermassive black hole that is billions of times heavier than our sun. After collecting a huge amount of data, they put it all together to create that famous image.

But what are we really looking at in that picture? It is not a photo of the black hole itself. The black hole is still in the middle, and it is still perfectly black. The glowing orange ring is not an Einstein Ring from a galaxy behind it. Instead, that is the super-hot gas and material (called an accretion disk) that is swirling around the black hole. This material is spinning at incredible speeds, almost the speed of light. The friction and intense gravity heat this gas to millions of degrees, causing it to glow brightly in radio light (which the EHT can see). The black part in the very center is the “shadow” of the black hole. This is the event horizon—the area where light is captured. We are seeing the black hole’s silhouette against the bright, glowing gas that surrounds it. This is like seeing the shadow of an invisible person standing in front of a bright bonfire. You do not see the person, but you see the “hole” in the firelight where they are standing.

What Other Ways Can We Find Black Holes?

Gravitational lensing is a powerful tool, but it is not the only way we find black holes. It requires a lucky alignment of a black hole and a bright object behind it. Astronomers have several other methods in their toolkit to hunt for these invisible objects. One of the most common ways is to simply watch how things move. We cannot see the black hole, but we can easily see the powerful effect of its gravity on any stars that are unlucky enough to be nearby.

Think about two ice skaters holding hands and spinning in a circle. You can see them both. Now, imagine one of the ice skaters is completely invisible. You would only see the visible skater. But they would not be still. You would see them spinning around very fast, seemingly orbiting an empty patch of ice. By watching the visible skater’s speed and the path of their orbit, you could figure out exactly how heavy their invisible partner must be. Astronomers do this all the time. They scan the sky for stars that are “dancing with a ghost.” They will find a normal, visible star that is moving very quickly in a tight orbit around… nothing.

By measuring the star’s movement, scientists can calculate the mass of its invisible partner. If the invisible partner is only a little heavy, it might be a normal, unlit star. But if the calculations show the invisible object is, for example, ten times heavier than our sun (but is completely dark), there is only one thing it can be: a black hole. This is exactly how we discovered the supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy. We cannot see it, but we can see a whole cluster of stars at the galaxy’s core. These stars are whipping around an empty point in space at millions of miles per hour. Their frantic dance is all the proof we need that a monstrous, invisible black hole (named Sagittarius A*) is holding them in its grip.

What Is an Accretion Disk?

Another key clue is that black holes are often very “messy eaters.” While some black holes might drift through space alone, many are in binary systems (paired with a normal star) or in busy areas with lots of gas and dust. The black hole’s powerful gravity can pull this material—gas, dust, or even parts of its neighboring star—toward it. But this material does not just fall straight in. Because it has some sideways motion, it gets caught in orbit and begins to spiral around the black hole, like water circling a drain.

This spinning, flat “pancake” of material is called an “accretion disk.” This disk is where the real action happens. As the gas and dust spiral closer and closer to the event horizon, the black hole’s gravity pulls it faster and faster. The material rubs against itself, creating an incredible amount of friction. This friction heats the gas in the disk to millions of degrees. For comparison, the surface of our sun is only a few thousand degrees. This superheated material glows with unbelievable brightness.

However, it gets so hot that it does not glow in the visible light we see with our eyes. It shines in high-energy light, like X-rays. Our atmosphere blocks X-rays from space, so scientists use special X-ray telescopes in orbit (like NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory) to scan the sky. When they find an extremely bright, flickering source of X-rays, it is a very strong sign that they are looking at an accretion disk. The black hole in the center is still perfectly dark, but its “dinner plate” of super-hot gas is one of the brightest and most violent things in the universe. We find the invisible black hole by seeing the X-ray “scream” from its last meal.

What Are Gravitational Waves?

There is one more way to detect black holes, and it is the newest and most amazing of all. This method does not use light at all. Instead, it “listens” to the vibrations of spacetime itself. This was another one of Albert Einstein’s predictions. He said that when truly massive objects (like black holes or neutron stars) move, they do not just bend space—they create ripples in the fabric of spacetime. These are called “gravitational waves.”

Think of spacetime as the calm surface of a giant pond. If you drop a small pebble in, it makes tiny ripples. If you have two massive boats speeding around and crashing into each other, they will create huge waves that travel all the way across the pond. This is what happens in space. When two massive black holes are orbiting each other, they are stirring up spacetime, sending out constant gravitational waves. As they spiral closer and closer, they move faster, sending out stronger and stronger waves. In the final moment when they collide and merge into one, they release a burst of powerful gravitational waves that travel across the universe at the speed of light.

For decades, we could not detect these waves; they are incredibly tiny by the time they reach us. But scientists built amazing detectors, like LIGO (in the United States) and Virgo (in Europe). These detectors are giant, L-shaped facilities with tunnels miles long. They shoot lasers down these tunnels and bounce them off mirrors. When a gravitational wave passes through Earth, it literally stretches and squeezes everything—including the detector’s tunnels. The change is smaller than the width of an atom, but the lasers are sensitive enough to measure it. In 2015, LIGO “heard” a “chirp” for the first time. It was the sound of two giant black holes colliding over a billion light-years away. We did not “see” them with a telescope; we felt the vibration of their collision. This was a brand new way to “sense” the universe and gave us final, undeniable proof that black holes are real.

Conclusion

So, how can we see a black hole? The simple answer is, we cannot. They are truly, perfectly invisible. Their gravity is so strong that they trap light itself, making it impossible to see them directly. But that does not mean they can hide from us. Scientists have become cosmic detectives, finding black holes by looking for the clues they leave behind.

We “see” them by watching how their powerful gravity bends the light from distant galaxies behind them, an effect called gravitational lensing. We “see” them by taking a picture of their “shadow” against the super-hot, glowing gas that is swirling right around their edge. We “see” them by watching nearby stars as they dance around an invisible, heavy partner. We “see” them by spotting the super-bright X-ray glow from their “accretion disk,” the last meal they are about to eat. And finally, we can even “hear” them when they crash together, by sensing the gravitational waves, the ripples they make in the fabric of space itself. Black holes may be dark, but they are far from hidden.

As our telescopes get more powerful and our detectors get more sensitive, we are finding more and more of these amazing objects. They are teaching us about gravity, the lives of stars, and how our entire universe works. As our cosmic “senses” continue to improve, what other amazing secrets do you think these invisible giants are waiting to show us?

FAQs – People Also Ask

What is an event horizon?

The event horizon is the “point of no return” around a black hole. It is not a physical surface, but a boundary. Once anything, including light, crosses this boundary, the black hole’s gravity is so strong that it can never escape.

Can a black hole suck in the whole universe?

No, a black hole cannot suck in the whole universe. A black hole’s gravity is only extremely strong very close to it. If our sun were suddenly replaced with a black hole of the same mass, Earth would not get sucked in; it would continue to orbit the black hole just as it orbits the sun.

What would happen if I fell into a black hole?

As you got closer, the gravity at your feet would be much stronger than the gravity at your head. This difference would stretch you out like spaghetti, a process scientists call “spaghettification.” Once you crossed the event horizon, you could never escape.

What is the ‘shadow’ of the black hole we saw in the picture?

The famous black hole picture from 2019 shows a glowing ring with a dark center. That dark center is the “shadow.” It is the black hole’s event horizon, which traps all light. We are seeing its silhouette against the backdrop of super-hot, glowing gas that is swirling around it.

How big are black holes?

Black holes can be many different sizes. “Stellar-mass” black holes are formed from a single, massive star and might be 10 or 20 times heavier than our sun, but only as wide as a city. “Supermassive” black holes are found at the centers of galaxies and are huge, weighing millions or even billions of times more than our sun.

Is there a black hole near Earth?

Yes, but none are close enough to be dangerous. The closest known black hole is named Gaia BH1, which is about 1,560 light-years away. The supermassive black hole at the center of our own galaxy, Sagittarius A*, is safely over 26,000 light-years away.

What is an Einstein Ring?

An Einstein Ring is a special case of gravitational lensing. It happens when a massive object (like a black hole) is perfectly lined up between us and a distant, bright galaxy. The black hole’s gravity bends the light from the background galaxy into a perfect, glowing circle or ring.

How do gravitational waves work?

Gravitational waves are “ripples” in the fabric of spacetime, much like waves in a pond. They are created when massive objects, like two black holes, move very fast or collide. These ripples travel across the universe at the speed of light, and we can detect them on Earth with special laser detectors like LIGO.

Why did the Event Horizon Telescope need to be so big?

To see something very small and very far away (like a black hole’s shadow), you need a telescope with extremely high “resolution” or sharpness. The only way to get that much sharpness is to build a giant telescope. By linking many radio dishes across the world, scientists created a “virtual” telescope as big as the entire planet.

What is Hawking radiation?

Hawking radiation is a theory from scientist Stephen Hawking. It suggests that, over a very, very long time, black holes are not completely black but can slowly “evaporate” by releasing tiny particles. For normal black holes, this process is incredibly slow and has not yet been observed.