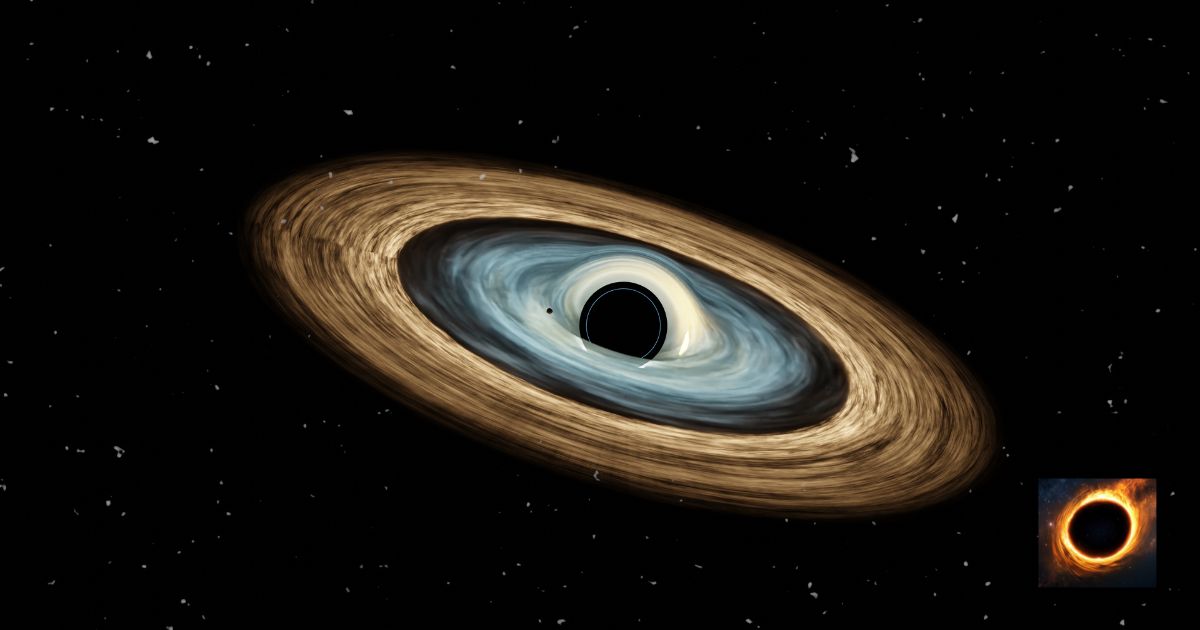

The universe is a truly massive place, filled with wonders that can sometimes sound a little bit scary. One of the most talked-about and mysterious objects in all of space is the black hole. For a long time, these were mostly a theoretical idea, something that came purely from deep scientific math. Now, we know they are very real, and our telescopes can even capture images of the hot, glowing material just before it falls inside. Black holes are the ultimate cosmic vacuum cleaners.

We know that black holes are everywhere. They are formed when a very large star runs out of fuel and collapses in on itself, squeezing all its material into a tiny spot. When this happens, its gravity becomes so unbelievably strong that nothing, not even light, can escape. Astronomers estimate there could be a staggering 100 million of these star-sized black holes roaming around in our own Milky Way galaxy. The majority of them are quietly floating alone, far away from any stars, which is why scientists call them “wandering” or “rogue” black holes. It’s easy to feel a little uneasy knowing that so many invisible, incredibly heavy objects are out there, potentially crossing paths with our Solar System.

When we consider the possibility of one of these hidden wanderers coming close to Earth, it raises a critical question: is our planet truly safe from such an encounter? The sheer number of these objects in our galaxy suggests that the possibility exists, even if the odds are incredibly small. The thought of a super-dense, invisible object hurtling toward us is certainly frightening, but what does the science actually say about this cosmic danger?

What Exactly Is a ‘Wandering Black Hole’ and Where Do They Come From?

A “wandering black hole,” or free-floating black hole, is exactly what it sounds like: a black hole that is traveling through space, completely unattached to a star or a galaxy center. You can think of it like a bowling ball rolling across a vast, empty sports field. The bowling ball is not tied down to any goalpost, it’s just moving freely. Most black holes are found in one of two places: either orbiting a nearby companion star, or sitting in the very center of a galaxy, like the supermassive one at the heart of our Milky Way called Sagittarius A*. The wandering ones, however, have been given a powerful kick and are now moving through interstellar space.

These black holes are created through a few natural, but violent, processes. The most common way involves the death of a truly massive star. When a star with a mass about twenty times greater than our Sun collapses, the explosion, called a supernova, is not always perfectly balanced. Imagine a rocket engine that fires a little bit harder on one side than the other. This uneven push gives the newly formed black hole an enormous, powerful “kick,” launching it away from its birthplace at high speeds, often tens of kilometers per second. Another way they are formed is when a black hole is part of a binary system (two objects orbiting each other) and is violently ejected during a complex three-body gravitational interaction with another star or another black hole. These events transform a stationary black hole into a galactic nomad, drifting silently across the galaxy.

Can Scientists Actually See These Invisible Objects in the Vastness of Space?

The great challenge with wandering black holes is that they are invisible. By definition, a black hole is so dense that light cannot escape its gravitational pull, making it impossible for us to point a telescope at it and see a bright object. If they don’t have an accompanying star to feed on, they are just dark objects moving through the dark void of space. This is why they were only theoretical for so long. However, scientists have figured out a clever trick to detect them using a concept from Albert Einstein’s work called gravitational microlensing.

Gravitational microlensing works like this: space and time are not a flat, empty stage, but a fabric that is warped by mass. Any massive object, like a black hole, warps this fabric. If a black hole passes directly between Earth and a distant star, the black hole’s gravity acts like a giant, temporary magnifying glass. It bends the light coming from the background star, making the star appear much brighter for a few weeks or months. Not only does the star get brighter, but its apparent position in the sky can also shift slightly, like a tiny wobble. By carefully measuring this temporary brightening and the slight positional shift, astronomers can calculate the mass of the invisible object that passed in front of the star, which helps them confirm it is indeed a black hole and not just a smaller, dim star. This method led to the first confirmed detection of a single, isolated stellar-mass black hole, located about 5,000 light-years away and moving at about $45$ kilometers per second.

How Close Would a Black Hole Need to Get to Seriously Harm Earth?

The key to understanding the danger is knowing that gravity is not a magical, sudden force; it simply depends on mass and distance. Despite their scary reputation, a black hole is just an object with gravity, like a star or a planet. If you were to instantly replace our Sun with a black hole that has the exact same mass as the Sun, absolutely nothing would change about our planet’s orbit. The Earth would not be sucked in, and we would continue to orbit the black hole exactly as we orbit the Sun right now. The main difference would be that we would freeze because there would be no more sunlight.

The danger only comes when a black hole passes extremely close to our Solar System. To cause a real problem, a wandering black hole would need to pass within the distance of the outer planets, like Jupiter or Saturn. At that proximity, its powerful gravity would begin to mess with the delicate, billion-year-old balance of the Solar System. The black hole’s gravity would tug on all the planets, especially the small ones like Earth, causing their stable orbits to become stretched, tilted, or even ejected out into deep space. The orbits of asteroids and comets would also be thrown into chaos, potentially sending a devastating barrage of icy objects hurtling toward the inner planets, including Earth. A direct impact or an extremely close flyby inside Earth’s orbit would be needed to truly “swallow” the planet, a scenario that is practically impossible.

What Are the Actual Odds of a Wandering Black Hole Encountering Our Solar System?

The likelihood of a black hole passing close enough to disrupt the Solar System is extremely, incredibly, astronomically small. You are thousands of times more likely to win a major lottery jackpot than to be harmed by a rogue black hole in your lifetime. To understand why, you need to appreciate the true scale of space. While there are an estimated $100$ million or more stellar-mass black holes in the Milky Way, our galaxy is also about $100,000$ light-years across. Space is not a crowded city street; it is a vast, nearly empty ocean, and every object is separated by immense distances.

Astronomers have done the math based on the estimated density of these objects and their average speeds. The chance of a black hole passing close enough to seriously disrupt Earth’s orbit (within the distance of Jupiter) over the entire $4.5$ billion year history of the Solar System is only about 1 in 10,000. The chance of such an event happening in a single human lifetime is so tiny that it’s often considered effectively zero. Even the nearest known black hole is thousands of light-years away, and the closest estimated free-floating black hole might be around a hundred light-years away. At that distance, its gravitational pull on Earth is completely negligible compared to the gravity of our own Sun.

What Other Dangers Would We Face from a Black Hole Approach?

While the direct gravitational threat is very low, if a black hole did manage to wander near the Solar System, the most immediate danger would be the mass ejection and chaos it would cause in the outer Solar System. Beyond the planets, our Solar System is surrounded by the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud, which are essentially massive reservoirs of icy comets and asteroids. These billions of objects are currently held in a very stable, gentle orbit by the Sun’s gravity.

A passing black hole, even one that doesn’t directly hit Earth, would send a huge gravitational shockwave through these outer regions. It would be like shaking a giant jar of marbles. The gravity would suddenly shift the paths of countless comets and asteroids, flinging them inward toward the Sun. This would result in a massive and prolonged comet bombardment of the inner planets, including Earth, potentially triggering an event much worse than the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. The good news is that this kind of disruption would still require a very close pass, and its effects on the outer parts of the Solar System would be noticeable long before the objects reached Earth, giving us centuries or even millennia of warning.

How Do Astronomers Know the Solar System Hasn’t Been Hit Before?

The history of Earth and the Solar System is the best evidence that we are safe. Our planet has been orbiting the Sun for roughly $4.5$ billion years in an extremely stable and predictable path. If a massive, rogue object like a black hole had passed close enough to cause major damage, the effects would be permanent and obvious. The planets would have highly elliptical (stretched) orbits, or their orbits would be tilted wildly compared to the neat, flat plane they currently occupy. The fact that the Solar System is so orderly is a testament to its long-term stability and the lack of a major gravitational disruption in the deep past.

Furthermore, we can look at the geological record of Earth. If the Solar System had been recently subjected to a “comet shower” caused by a passing black hole, there would be evidence in the form of multiple, widespread impact craters dating back to the same era. While Earth has certainly been hit by asteroids and comets, the impact record does not show any signs of a single, catastrophic, billion-year-long period of continuous bombardment that a black hole flyby would create. The orderly nature of our celestial neighborhood and the historical stability of Earth’s geology are powerful, practical arguments against a current danger from wandering black holes.

What Future Discoveries Will Help Us Track These Hidden Threats?

The biggest advancement in tracking these hidden objects comes from new telescope technology and better methods for gravitational microlensing. For a long time, detecting a black hole was a lucky accident, relying on the alignment of a black hole and a background star, which is a rare event. However, observatories are becoming much better at this kind of wide-field, continuous monitoring. The development of very large, next-generation telescopes is designed to quickly scan huge areas of the sky, spotting hundreds of thousands of stars at once.

One major project being developed is specifically designed to conduct a massive census of the sky, looking for the tell-tale temporary brightening caused by microlensing. As these new tools come online, astronomers expect to go from confirming one or two of these events to confirming dozens, giving us a much more accurate map of where these wandering black holes are, how fast they are moving, and how numerous they truly are. Knowing their population density and average velocity is the first step in creating a precise prediction for any object that might eventually come close to our Solar System, even if that event is millions of years in the future. Better data means better safety.

Conclusion

The idea of a “wandering” black hole is certainly one of the most dramatic and unsettling scenarios that space can offer. It is true that our Milky Way galaxy is filled with possibly a hundred million of these invisible, star-sized gravitational remnants, silently drifting through the cosmic void. However, the immense emptiness of space is our greatest shield. The odds of a close encounter—one that would be close enough to truly disrupt the Earth’s orbit or trigger a devastating comet storm—are so incredibly low that they fall into the realm of things we do not need to worry about in our lifetimes. Our Solar System’s long, stable history and the orderly orbits of the planets are the most solid evidence that we are in a safe, quiet pocket of the galaxy. New, powerful telescopes are only going to make us safer by allowing us to finally map out where these wanderers are and confirm their paths long before they could ever become a threat.

If the universe is so full of wandering black holes, could there be one lurking just beyond the known boundaries of our Solar System right now?

FAQs – People Also Ask

How far away is the closest known black hole to Earth?

The closest confirmed black hole to Earth is currently believed to be Gaia BH1, which is about $1,560$ light-years away from us. A light-year is the distance light travels in one year, which is about $9.5$ trillion kilometers, so this black hole is an enormous distance away. At this range, its gravitational effect on our Solar System is completely unmeasurable, meaning it poses absolutely no threat to us. Scientists are constantly searching for closer ones, but the sheer scale of the galaxy makes it unlikely that one is truly right next door.

If a black hole passed through our Solar System, would it suck in the Sun?

No, a black hole passing through the Solar System would not simply “suck in” the Sun. The idea that black holes act like giant vacuum cleaners is a common misunderstanding. For the Sun to be swallowed, it would need to pass incredibly close to the black hole, essentially grazing its event horizon. The much more likely effect of a passing black hole would be a violent gravitational disruption of the orbits of all objects, including the Sun. The Sun might be flung out of the Solar System entirely, or its orbit around the galactic center might be changed drastically, but it would not just be “sucked in” from a distance.

Can a star turn into a black hole while it is still alive?

No, a star can only turn into a black hole after it has died. A star is kept stable by a perfect balance: the force of its own gravity pulling everything inward is balanced by the massive outward pressure created by the nuclear fusion reactions (like a continuous hydrogen bomb) happening in its core. When the star runs out of fuel for fusion, the outward pressure stops, and there is nothing left to fight the crushing force of gravity. If the star is massive enough (about $20$ times the mass of our Sun or more), gravity wins completely, and the star collapses down into a black hole.

How are wandering black holes different from the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy?

Wandering black holes are typically stellar-mass black holes, meaning they have the mass of a single star, usually between $5$ and $100$ times the mass of our Sun. They are small and drift alone. The supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy, called Sagittarius A*, is a completely different kind of object. It is a giant, weighing about 4 million times the mass of our Sun, and it stays fixed at the gravitational center of the Milky Way, acting as the anchor around which the entire galaxy rotates.

Would we see any warning signs if a black hole was approaching Earth?

Yes, we would likely have a warning that could last for thousands or even millions of years. As a massive, invisible object like a black hole approached the outer edge of our Solar System, its gravity would begin to affect the orbits of the outer planets, like Neptune and Uranus, and the distant comets in the Oort Cloud. These changes, although very slight at first, would be measurable by astronomers. The orbits of distant stars would also appear to wobble very slightly due to the black hole’s gravity, and the microlensing effect would become stronger and more frequent with background stars as the black hole got closer.

Do black holes move very fast through space?

Yes, wandering black holes can move quite fast, often much faster than ordinary stars. They are generally moving at speeds of tens or even hundreds of kilometers per second relative to their surroundings. This high speed is often the result of the violent supernova explosion that created them, which can give the black hole a powerful recoil kick, much like a gun firing a bullet. This high velocity is part of what allows them to escape the area where they were born and wander through the galaxy.

Is it possible for a black hole to pass right through the Earth?

In theory, yes, but the effects would be catastrophic. If a stellar-mass black hole somehow passed directly through the Earth, its intense gravity would cause an immediate, violent disruption of the planet’s internal structure. The tidal forces from the black hole would be so strong that they would stretch and squeeze the Earth’s material, likely shattering the planet and heating the remnants to extreme temperatures. It would not be a clean pass, but a planetary-scale destruction event. The probability of this is negligible, as the black hole’s actual physical size is incredibly small, often less than the size of a city.

What is the event horizon of a black hole?

The event horizon is the boundary or point of no return around a black hole. It is not a physical surface, but an invisible line in space. If any matter, light, or signal crosses this line and goes inward, the force of gravity is so strong that the velocity needed to escape is faster than the speed of light. Since nothing can travel faster than light, anything that crosses the event horizon is permanently trapped, which is why a black hole appears black.

Could a wandering black hole eventually be captured by our Sun’s gravity?

It is possible, but highly unlikely given their speed. For a wandering black hole to be captured by the Sun, it would need to be moving very slowly when it got close, allowing the Sun’s gravity to successfully grab it and pull it into a permanent orbit. Because most wandering black holes are moving at very high speeds, they would simply pass by the Sun and keep moving, their trajectory only slightly bent by the Sun’s gravity, much like a comet that only passes through the Solar System once.

Have astronomers found any black holes that are truly alone in the dark?

Yes, using the gravitational microlensing technique, astronomers have successfully identified and measured the mass of at least one free-floating stellar-mass black hole that is truly alone in space. This confirmed detection, which happened a few years ago, was a huge step forward because it moved the concept of a “rogue” black hole from pure theory into observable fact. It proved that these objects exist in isolation and that we have a method to detect them, which is crucial for future safety mapping.